Listen to Episode 193 on PodBean, YouTube, Spotify, or wherever you listen to your favorite podcasts!

Animals get around in a variety of ways, but some are particularly bouncy. This episode, we discuss the various styles, adaptations, and ancient evidences of Hopping.

In the news

Different structures of feathered and non-feathered dinosaur skin

425-million-year-old marine worm was among the last of its kind

Diverse assemblage of Cretaceous monotremes in an Australian site

Convergent evolution of ant-attracting nectaries in ferns and flowering plants

Hopping

Terrestrial animals get around with a variety of gaits – that is, patterns of locomotion – including walking, trotting, galloping, etc. Several of these gaits are particularly bouncy motions that we might call “hopping.”

Top left: A rabbit bounding. Image by Lauris Rubenis, CC BY 2.0

Top middle: A jumping toad. Image by N p holmes, CC BY-SA 3.0

Top right: A pronking springbok. Image by Yathin sk, CC BY-SA 3.0

Bottom: Kangaroo hopping sequence. Image by Charles J. Sharp, CC BY-SA 4.0

Some animals are skilled jumpers, and their hopping is a series of consecutive single jumps, like many insects and frogs. Others, like rabbits, move by bounding, a type of hopping locomotion that maintains speed and momentum from each hop to the next. Pronking is a type of bouncy motion seen in certain ungulates like deer and antelope, which push off the ground with all four legs at once.

And then there are the bipedal hoppers, animals that move around by bouncing only on their hind limbs. This gait has evolved several separate times among mammals.

Top left: Kangaroo rat. Image by Bcexp, CC BY-SA 4.0

Top middle: Hopping mouse. Image by Boyd Essex, CC BY 4.0

Top right: Jerboa. Image by Mohammad Amin Ghaffari, CC BY 4.0

Bottom left: Springhare. Image by Revolutionrock1976, CC BY-SA 4.0

Bottom right: Grey kangaroo. Image by Mark Wagner, CC BY-SA 3.0

Hopping is typically a high-speed form of locomotion, and most hopping animals use different gaits at lower speeds. For some animals, hopping is a rapid and unpredictable way to avoid predators; for others, it’s useful for navigating complex environments. Pronking specifically seems to be an important display behavior. And then some hoppers are simply limited by anatomy – many birds are so well adapted for hopping around in trees that must also hop around while on the ground.

Fossil Hoppers

Hopping animals, especially bipedal hoppers, often have specialized anatomy of the leg and foot bones. Similar anatomy in fossils has led paleontologists to infer hopping locomotion in a handful of extinct species, particularly mammals, as far back as the Cretaceous Period.

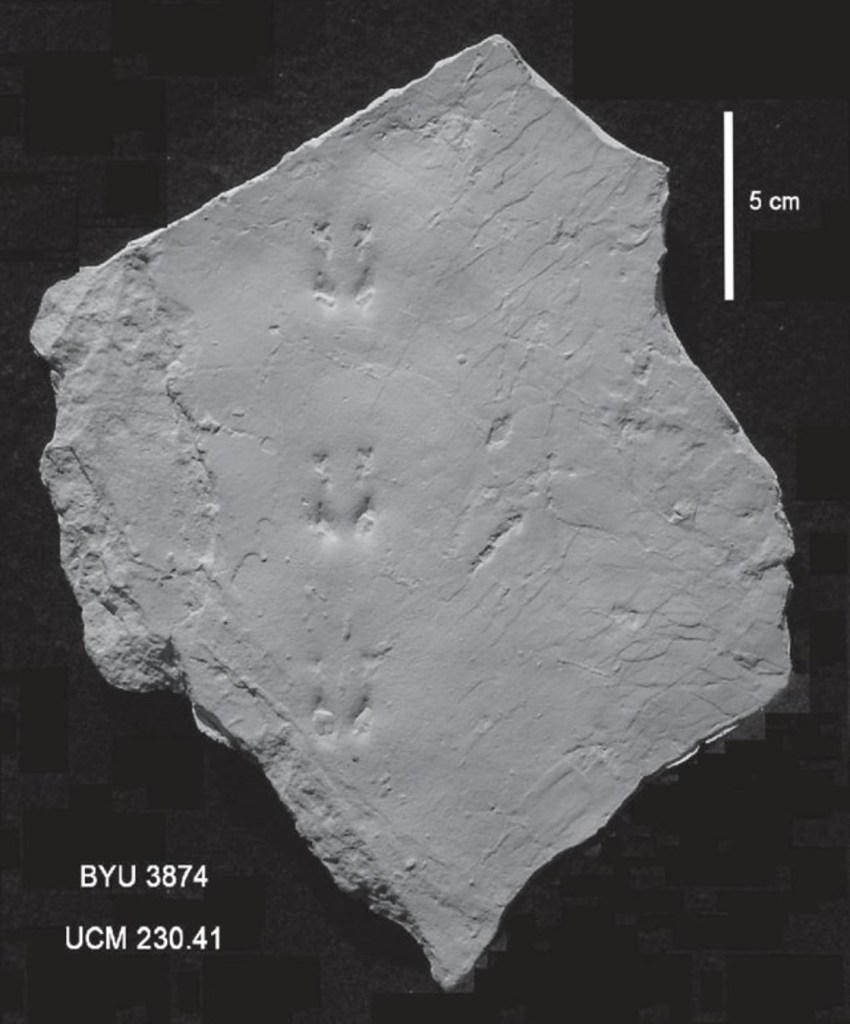

But the best evidence of hopping locomotion in the fossil record comes from footprints. Hoppers leave distinctive tracks. Bipedal hopping, for example, leaves behind a series of paired footprints with no handprints; while bounding creates paired handprints just behind paired footprints.

Right: Modern tracks of a bounding mammal in snow. Notice the paired footprints in front of the paired handprints. Image from Milner et al 2022.

Hopping trackways are rare in the fossil record, but tracks of bounding and bipedal hopping mammals (and near-mammals) are known from the Americas and Asia as far back as the Late Jurassic. Hopping trackways of frogs are especially common in certain Cretaceous formations in Korea, and a handful of tracks from Jurassic Africa have been interpreted as possibly hopping reptiles.

Image from Lockley and Milner 2014.

Image from Lockley and Milner 2014.

Learn more

Why do mammals hop? Understanding the ecology, biomechanics and evolution of bipedal hopping (technical, open access)

Conquering the world in leaps and bounds: hopping locomotion in toads is actually bounding (technical, open access)

To Hop or Not to Hop? The Answer Is in the Bird Trees (technical, open access)

Locomotion in Extinct Giant Kangaroos: Were Sthenurines Hop-Less Monsters? (technical, open access)

Pleistocene small-mammal and arthropod trackways from the Cape south coast of South Africa (technical, open access)

The ichnotaxonomy of hopping vertebrate trackways from the Cenozoic of the Western USA (technical, open access)

Walking, running, hopping: Analysis of gait variability and locomotor skills in Brasilichnium elusivum Leonardi, with inferences on trackmaker identification (technical, paywall)

Anuran (frog) trackways from the Cretaceous of Korea (technical, paywall)

Korean trackway of a hopping, mammaliform trackmaker is first from the Cretaceous of Asia (technical, paywall)

__

If you enjoyed this topic and want more like it, check out these related episodes:

We also invite you to follow us on Facebook or Instagram, buy merch at our Zazzle store, join our Discord server, or consider supporting us with a one-time PayPal donation or on Patreon to get bonus recordings and other goodies!

Please feel free to contact us with comments, questions, or topic suggestions, and to rate and review us on Spotify or Apple Podcasts!

Leave a comment