Listen to Episode 222 on Podbean, YouTube, Spotify, or wherever you listen to your favorite podcasts!

They’re among the tiniest of mammals and they live some of the most extreme lifestyles. This episode, we explore the extraordinary habits and evolution of Shrews.

In the news

Smallmouth bass are out-evolving efforts to get rid of them

“Impaled” Jurassic fish choked to death on cephalopod shells

Galápagos tomatoes have “re-evolved” ancestral toxins

Canadian rock formation might be the oldest known Earth rocks

Shrews: Surprisingly Specialized

On the outside, shrews seem like fairly standard small mammals, but the details of their anatomy and lifestyle are highly specialized.

Shrews belong to the family Soricidae, closely related to hedgehogs, moles, and other small mammals (but not closely related to elephant shrews, treeshrews, marsupial shrews, or various other small mammals that share the name “shrew”). With around 500 species across most continents, shrews are one of the most diverse mammal families. Most shrews live in moist, warm forests hunting for bugs in the soil and leaf litter, but there are a variety of species adapted for drier habitats, colder habitats, and lives of burrowing, climbing, or even swimming.

Top right: Greater white-toothed shrew (Crocidura russula). Image by Rasbak, CC BY-SA 3.0

Bottom left: Common shrew (Sorex araneus). Image by Soricida, CC BY-SA 3.0

Bottom right: Etruscan shrew (Suncus etruscus). Image by Trebol-a, CC BY-SA 3.0

Shrews are very small. The tiniest species are Etruscan shrews, which weigh around 2.5 grams, a contender for the smallest living mammal species. The largest living shrews, such as Asian house shrews and Hero shrews, can weigh a whopping 100 grams or more (the size of a small rat).

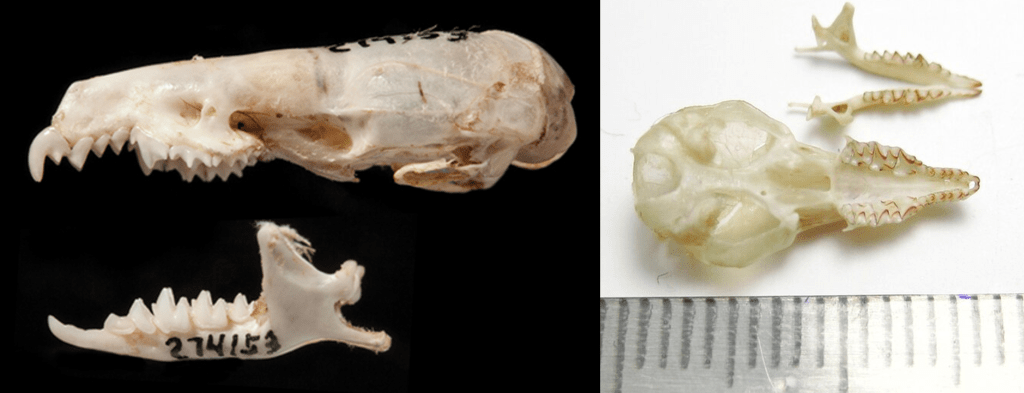

Inside their heads, shrews have very distinctive skulls, with an unusual jaw anatomy that allows them to chew with greater flexibility, multi-cusped teeth that include forward-protruding incisors, and large braincases. Many shrews in the soricinae subfamily also incorporate iron deposits into the tips of their teeth, giving the teeth extra durability and a distinctive red color.

Right: Skull of a Caucasian pygmy shrew (Sorex volnuchini). Image by Nikita Gerasin, CC BY 4.0

Being so small, shrews require a very high metabolism to maintain a livable body temperature. They eat most of their own body weight in food per day, and they hunt at most times of the day and night. Shrews are so dependent on their voracious diets that an average sized shrew will starve to death in only about 9-10 hours without food (among biologists, shrews are notoriously difficult to trap for study).

Many species of shrews are also known to be venomous, delivering venom along their protruding incisors. Their venom causes paralysis, respiratory distress, and other unpleasant effects that help them take down larger prey like frogs and other small mammals. Some shrews use their venom to immobilize prey that they can then stash away for later.

Image from Storch and Qiu 2004

Shrew-like mammals – probably ancestors or cousins of true shrews – are known from the Eocene Epoch (around 45 million years ago) of North America. True shrews originated later in the Oligocene Epoch and then gave rise to the beginnings of our modern diversity in the Miocene Epoch, starting around 20 million years ago.

Most shrew fossils are limited to teeth and lower jaws, although there are well-preserved exceptions. The fossil record also includes evidence of diverse evolutionary trajectories in the past, including shrews adapted for snail-eating, possible fruit-eating shrews, and a population of ancient European shrews that became island “giants” (but still only around 30 grams, giant compared to their tiny cousins).

And shrew fossils are also abundant at the Gray Fossil Site, where this episode’s guest, Derek, uses their remains to understand the dietary diversity of ancient shrew species.

Learn More

The Shrews of the World, Tetrapod Zoology (semi-technical)

The origin and evolution of shrews (technical, open access)

Distribution of shrews in time and space (technical, open access)

Deciphering an extreme morphology: bone microarchitecture of the hero shrew backbone (technical, open access)

Venom Use in Eulipotyphlans: An Evolutionary and Ecological Approach (technical, open access)

__

If you enjoyed this topic and want more like it, check out these related episodes:

We also invite you to follow us on Facebook or Instagram, buy merch at our Zazzle store, join our Discord server, or consider supporting us with a one-time PayPal donation or on Patreon to get bonus recordings and other goodies!

Please feel free to contact us with comments, questions, or topic suggestions, and to rate and review us on Spotify or Apple Podcasts!

Leave a comment