Listen to Episode 226 on Podbean, YouTube, Spotify, or wherever you listen to your favorite podcasts!

There is perhaps no more famous symbol of extinction than these birds. This episode, we discuss the tragic story and subsequent scientific discoveries of Dodos.

In the news

A new predatory terrestrial croc from Argentina

The oldest known ankylosaur is extremely spiky

Ancient lineage of sea turtles discovered in Syria

Convergent evolution in cave fish of eastern North America

The Way of the Dodo

Dodos (Raphus cucullatus) were flightless birds native to the Mascarene island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. Their tragic story is probably the single most famous tale of recent extinction. The first record of human observation of dodos is from 1598, and the last is from 1662. Within a century of humans settling on their island, dodos had become extinct.

Image BazzaDaRambler, CC BY 2.0

Like many island birds, dodos were large (at least 10-14 kg) and flightless. Also like many island birds, they were well-adapted to the specific conditions of their island home and ill-prepared for the dramatic changes that humans brought to their ecosystem. Early settlers on Mauritius hunted dodos and cleared forests, which certainly didn’t help the birds, but by far the biggest impact came from introduced species of goats, deer, rats, pigs, and monkeys which devastated local habitats. Dodos were only one of the many species of Mauritian wildlife to go extinct in the following centuries.

Right: Painting of a dodo head by Cornelis Saftleven from 1638, possibly one of the last illustrations made of a live dodo.

Sadly, no detailed scientific study of dodos was performed while they were alive. Surviving records of the species include a variety of illustrations, written descriptions from visitors to Mauritius, reports of live dodos being transported to other countries, and a handful of heads and feet preserved in museums.

Bottom: A dodo skull, one of only two brought to Europe from Mauritius in the 1600s. Image by FunkMonk, CC BY-SA 3.0

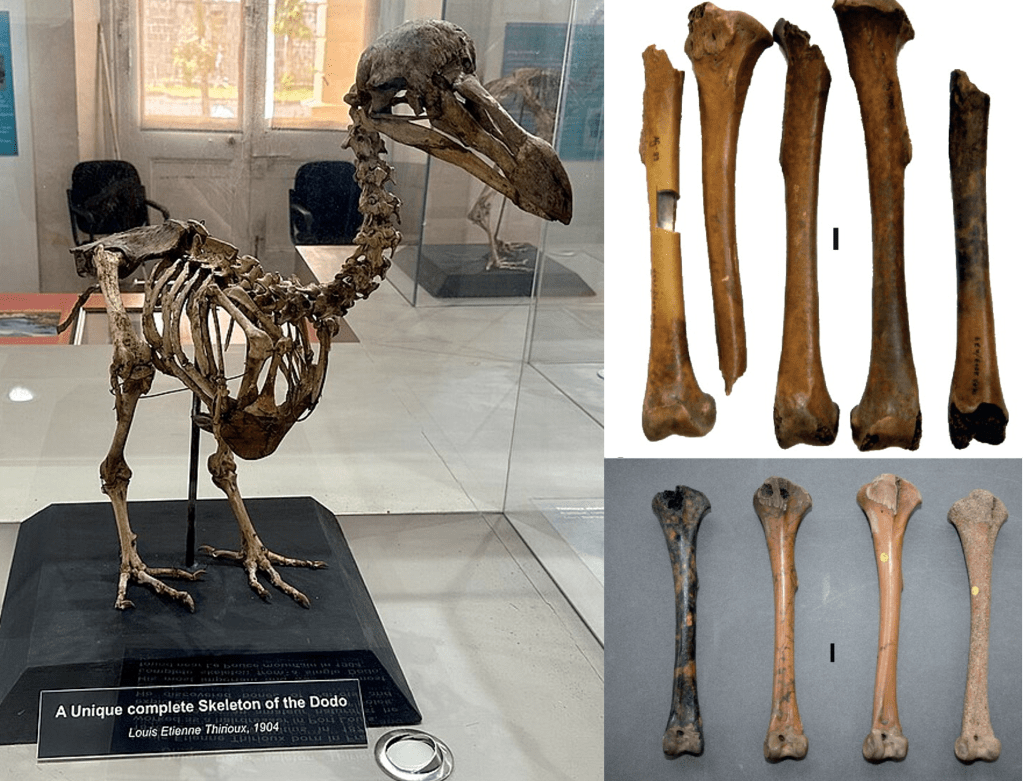

Ironically, even though humans knowingly lived alongside dodos for nearly a century, most of our knowledge about these birds comes from fossils. Starting in the mid-1800s, naturalists have found fossilized remains on the island of Mauritius, including a pair of nearly complete dodo skeletons found by Louis Thirioux in the early 1900s. Most of the known fossil record of dodos comes from the Mare aux Songes marsh near the island’s southeast coast, where scientists have uncovered the remains of many recently extinct Mauritian species, including giant tortoises, giant skinks, a variety of birds, and hundreds of dodo bones, all dating to around 4,000 years ago.

Right (top and bottom): A variety of fossil dodo leg bones from Mares aux Songes on Mauritius. Image from Rijsdijk et al 2016.

Dodos stood about a meter tall, with small wings and a large hooked beak that was probably used for crushing seeds, fruits, and aquatic invertebrates. Their wings, though small, were powerfully muscled and probably used for flashy displays or physical combat with rivals. Their legs are also powerful, likely able to carry them swiftly over the ground – which is consistent with written reports that describe the birds as being difficult to catch.

The rapid extinction of dodos led to the interpretation of them as slow, awkward, and unintelligent animals, but their skeletons reveal a suite of unique adaptations that allowed them to thrive on their home island.

Left: Victoria Crowned Pigeon (Goura victoria), native to the New Guinea region, the largest living species of pigeon. Image by Jörg Hempel, CC BY-SA 3.0

Right: Nicobar pigeon (Caloenas nicobarica), native to islands and mainland of Southeast Asia. Image by cuatrok77, CC BY 2.0

Dodos were pigeons, as revealed by DNA extracted from fossils and preserved specimens. They belong to the Columbiformes (pigeons and doves) and more specifically to a subgroup called Raphini, which includes many species of ground-dwelling island pigeons.

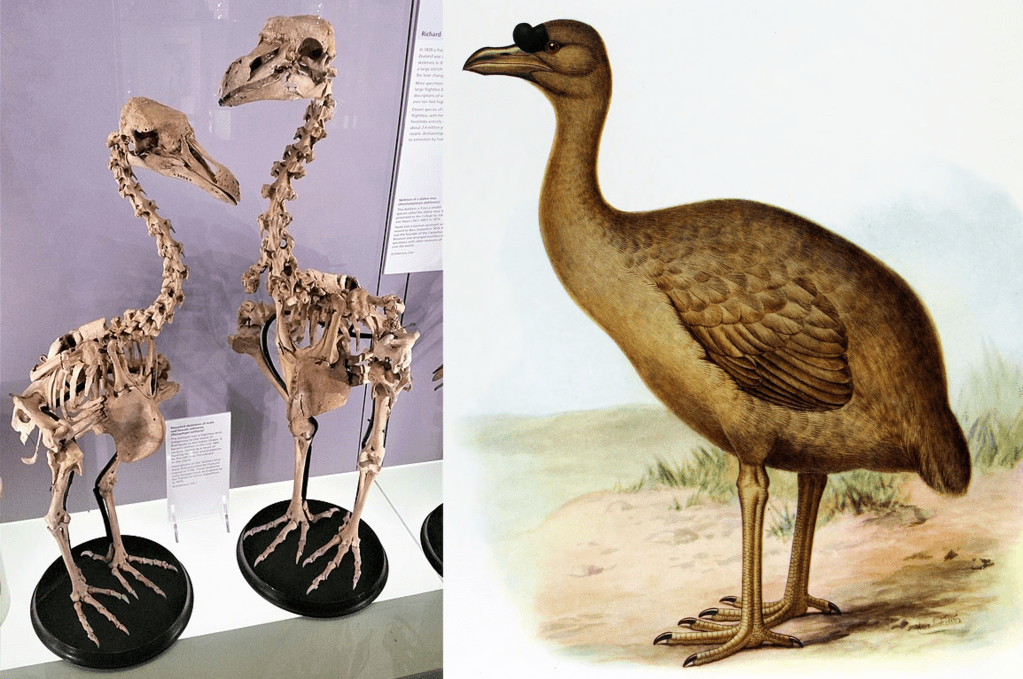

Dodos were one of two species within the even smaller group Raphina, the Mascarene Islands Giant Pigeons. Their sister species within this group were the Rodrigues solitaires (Pezophaps solitaria), native to the Mascarene island of Rodrigues, not far from Mauritius. Like dodos, solitaires were large, flightless birds, and like dodos, they went extinct shortly after their home island became of interest to humans.

Right: Illustration of Rodrigues solitaire by Frederick William Frohawk in 1907, based on previous descriptions and drawings.

Fortunately, many solitaire fossils have been found on the island of Rodrigues, which has allowed paleontologists to interpret their lifestyle. They likely had a similar diet and habitat as dodos, although the solitaires exhibit an extraordinary degree of sexual dimorphism (males appear to have been much larger than females) and they have bony knobs on their wings that they apparently used to fight each other.

Right: Illustration of a dodo from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, illustrated by John Tenniel in 1865.

After their extinction, dodos became famous, thanks in large part to their inclusion in a variety of famous paintings and Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Today, they are most famous as a symbol of extinction, a reminder of how quickly and irreversibly our own actions can change the ecosystems around us.

Learn More

When did the dodo become extinct?

A review of the dodo and its ecosystem (technical, open access)

Bone histology sheds new light on the ecology of the dodo (technical, open access)

Dead as a dodo: The fortuitous rise to fame of an extinction icon (technical, open access)

__

If you enjoyed this topic and want more like it, check out these related episodes:

- Episode 4 – Island Evolution

- Episode 55 – The “Sixth Extinction” (Modern Biodiversity Crisis)

- Episode 108 – Penguins

We also invite you to follow us on Facebook or Instagram, buy merch at our Zazzle store, join our Discord server, or consider supporting us with a one-time PayPal donation or on Patreon to get bonus recordings and other goodies!

Please feel free to contact us with comments, questions, or topic suggestions, and to rate and review us on Spotify or Apple Podcasts!

Leave a comment