Listen to Episode 229 on Podbean, YouTube, Spotify, or wherever you listen to your favorite podcasts!

Generally speaking, it’s not a good idea to mess with ants, but some animals have made a whole lifestyle out of it. This episode, we discuss the deep history and repeated evolution of Myrmecophagy (Ant-Eating).

In the news

Unusual trace fossil might represent a rock hyrax butt-drag

The oldest known fossil leech is missing some key leech-parts

Footprints of a Neanderthal family on the coast of Portugal

The incredible shrinking genomes of Canary Island spiders

Maybe Try a Few

Many animals occasionally feed on ants and termites. These insects are extraordinarily abundant and pretty easy to gobble up, and they tend to gather in big colonies. But some animals are specialists: the term myrmecophage typically refers to species whose diet consists almost entirely of ants or termites (termite-eating is sometimes specifically called termitophagy).

Top left: Giant anteater. Image by Malene Thyssen, CC BY-SA 3.0

Bottom left: Silky anteater. Image by Quinten Questel, CC BY-SA 3.0

Middle: Southern tamandua. Image by Sinara Conessa, CC BY 2.0

Right: Northern tamandua. Image by Dirk van der Made, CC BY-SA 3.0

The most famous ant-eaters are … anteaters! Species within the group Vermilingua, native to Central and South America and closely related to sloths and armadillos, are highly specialized myrmecophages. They have long, tube-like mouths with no teeth, very long tongues covered with sticky saliva and tiny hooks for scooping ants right out of their homes, and massive claws for digging into anthills. Anteaters even have stomachs that operate similarly to a bird’s gizzard, grinding up ants with hard tissues and ingested grit. Most living anteaters hunt for food in trees, while giant anteaters stick to the ground.

Top left: Aardvark (Orycteropus afer). Image by Kelly Abram, CC BY 4.0

Top middle: Tailless tenrec (Tenrec ecaudatus). Image by Markus Fink, CC BY-SA 3.0

Top right: Indian pangolin (Manis crassicaudata). Image by A. J. T. Johnsingh, CC BY-SA 4.0

Bottom left: Naked-tailed armadillo (Cabassous tatouay). Image by Enrique González , CC BY 4.0

Bottom middle: Elephant shrew (Rhynchocyon petersi). Image by Joey Makalintal, CC BY 2.0

Bottom right: Short-beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus). Image by JJ Harrison, CC BY-SA 3.0

But anteaters aren’t the only ant-eaters. Dedicated myrmecophagy has evolved at least a dozen times among mammals alone. Each time, these lineages have convergently evolved a similar suite of features: long tongues, tooth-less mouths, large claws, and more. Some species, like pangolins, have even evolved similar genetic changes that boost their ant-digesting abilities.

The fossil record of ant-eaters is pretty sparse. Most ant-eating mammals are relatively small-bodied and have a relatively small number of species, and their ancestors didn’t leave much in the fossil record. There are a handful of fossil anteaters known from South American fossil sites over the last 20 million years or so, which have similar skull features as living species.

There’s also the unique case of Eurotamandua, a species from the Eocene Messel Pit in Germany, once thought to have been an early anteater but now considered more closely related to pangolins. At over 40 million years old, Eurotamandua is among the oldest known dedicated myrmecophagous mammals.

There are ant-eaters outside of mammals, as well. Some lizards, such as the thorny devils of Australia and the horned lizards of North America, are primarily ant-eaters, though they use a very different strategy from their mammalian counterparts, often licking up ants one at a time right off the ground.

Dinosaurs, too, might have had myrmecophagous members. Certain species within the Alvarezsauridae, such as Mononykus and Shuvuuia, had small, simplified teeth and large claws on their hands that seem to have been well-suited for digging. These dinosaurs are generally suspected to have dined like modern anteaters on some of the very earliest ant and termite colonies back in the Cretaceous Period.

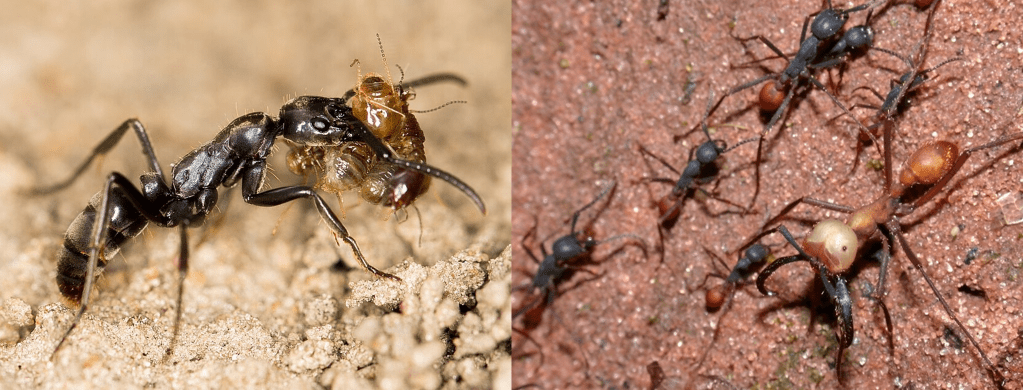

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the most accomplished eaters-of-ants are other ants. Many species of army ants, among others, are dedicated raiders of ant or termite colonies. Some species of ants live within or nearby termite mounds and dine upon the denizens. There are also ant-eating centipedes, spiders, beetles, and more.

Right: Eciton burchellii, army ants that hunt other ants. Image by Alex Wild\

It isn’t easy to eat ants – in fact, most species would rather avoid them – but if you can manage it, there’s lot of food to be had out there.

Learn More

Mammals Have Evolved Into Anteaters at Least 12 Times Since The Dinosaurs

How anteaters lost their teeth

Myrmecophagy in lizards (technical, open access)

The predatory behavior of ants (technical, open access)

First fossil skull of an anteater and the myrmecophagid diversification (technical, open access)

Growth and miniaturization among alvarezsauroid dinosaurs (technical, open access)

__

If you enjoyed this topic and want more like it, check out these related episodes:

We also invite you to follow us on Facebook or Instagram, buy merch at our Zazzle store, join our Discord server, or consider supporting us with a one-time PayPal donation or on Patreon to get bonus recordings and other goodies!

Please feel free to contact us with comments, questions, or topic suggestions, and to rate and review us on Spotify or Apple Podcasts!

Leave a comment