Listen to Episode 232 on Podbean, YouTube, Spotify, or wherever you listen to your favorite podcasts!

Today, bony animals are some of the most diverse organisms on Earth, but it wasn’t always that way. This episode, we explore what modern and fossil species have to tell us about Vertebrate Origins.

In the news

An algorithmic approach to identifying aquatic animals

Machine learning helps to identify early traces of life on Earth

Detailed info about the jaws of Dunkleosteus

First look at a complete Neanderthal nasal passage

All Bones About It

Vertebrates are, simply put, animals with bones. This group includes all living fish and their many land-dwelling descendants. Typical vertebrate features include a bony skull and vertebrae that protect their segmented brain and extensive spinal cord; paired limbs; paired sensory organs on a well-defined head; and plenty more.

Top left: Chimaeras are among the most basal living vertebrates. Image by Catarino et al 2020. CC BY 4.0

Bottom left: Lancelets are very basic chordates, just outside of true vertebrates. Image by Hans Hillewaert, CC BY-SA 4.0

Right: Sea squirts are tunicates, the closest living relatives of vertebrates. Image by Nick Hobgood, CC BY-SA 3.0

Vertebrates belong to a larger group called chordates, which also includes lancelets – a small group of tiny, worm-like animals that live on the seafloor – and tunicates – a diverse group of mostly bag-like gelatinous marine animals. Vertebrates, in turn, contain two major living groups: cyclostomes, a handful of species of jawless fish, and gnathostomes, jawed fish and all of their descendants (so, nearly all living vertebrates).

Left: A lamprey. Image by Tilt Hunt, CC BY-SA 3.0

Right: A hagfish. Image by Lmozero, CC0

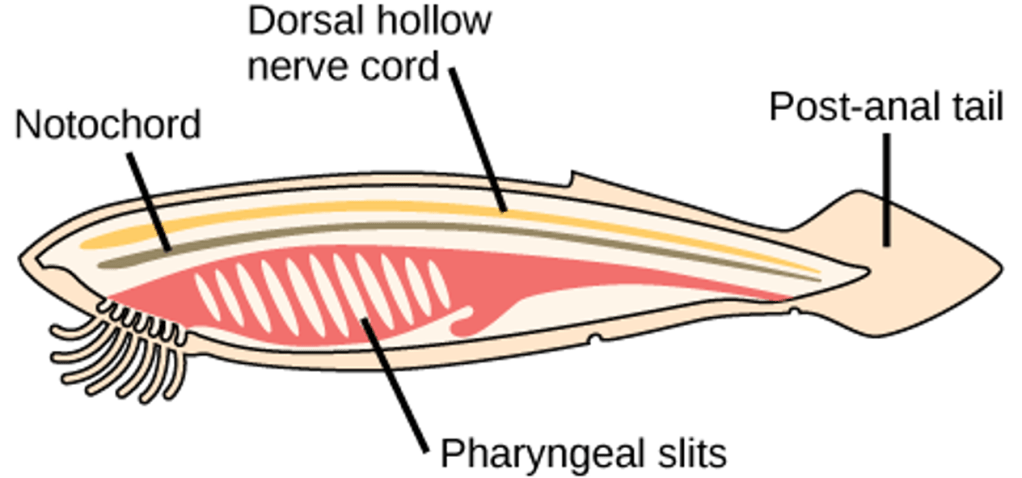

Chordates are united by a handful of specific features that reflect the fundamental way their bodies develop. They have a notochord, a stiff protein rod that strengthens the body axis; a nerve cord above the notochord; a muscular tail that extends beyond the anus; and pharyngeal slits behind the mouth which connect the body cavity to the outside world; among others.

All of these features are present in lancelets at every life stage, in most tunicates only as larvae, and in vertebrates only as embryos. As vertebrates develop, the notochord is replaced by the bony spine, the nerve cord expands into the brain and spinal cord, and the pharyngeal slits become gills (or, in tetrapods, parts of the jaws and throat). And of course, some of us vertebrates have even lost our tails. But deep in our ancestral features, we’re all chordates.

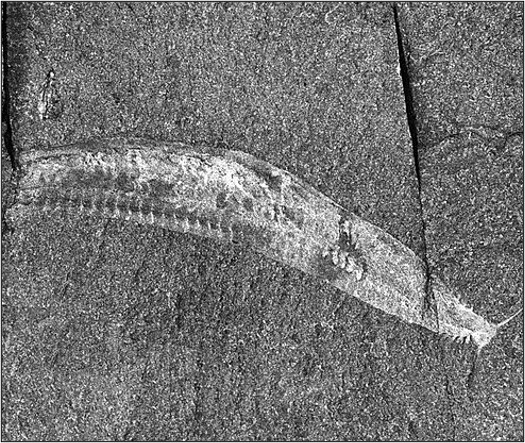

The transition from early chordates to the first true vertebrates is mostly preserved in a handful of exceptional Cambrian fossil sites, namely the Burgess Shale in Canada and the Chengjiang locality in China. At these sites, soft-bodied animals are preserved as thin layers of carbon, the remains of organisms pressed gently between sediment layers. These fossils reveal the shape of the body and even delicate details like musculature and internal organs.

The most famous of these fossils is Pikaia, from the Burgess Shale. Roughly the size and shape of a lancelet, Pikaia possesses a mixture of chordate features (including gills, segmented musculature, a notochord, and a dorsal nerve cord) with some non-chordate features (it lacks a tail and is covered in a protein cuticle). Along with a handful of other Cambrian critters, Pikaia represents either the earliest chordates or a very close cousin of the earliest chordates.

Bottom left: The probably early chordate Yunnanozoon from Chengjiang. Image by Mussini et al 2024, CC BY 4.0

Top right: The early vertebrate Myllokunmingia from Chengjiang. Image by Saleh et al 2022, CC BY 4.0

Bottom right: The early vertebrate Metaspriggina from the Burgess Shale. Image by Stefan Walkowski, CC BY-SA 4.0

The most famous early vertebrate fossils are those of Haikouichthys, the so-called “first fish,” known from Chengjiang. Haikouichthys and a handful of Cambrian relatives are somewhat similar to living lampreys, possessing among them paired eyes and nostrils on a distinct head containing a cartilage skull.

The exact relationships of these Cambrian creatures are heavily debated, but they provide a clear overall picture: a global group of lancelet-like early chordates in the early-to-middle Cambrian, and a global group of lamprey-like early vertebrates in the middle-to-late Cambrian. After the Cambrian, the fossil record is full of a diversity of jawless fish, including the eel-like conodonts and the armored ostracoderms, which variously develop mineralized scales and tooth-like structures, paired fins, and larger bodies. Then, by the Devonian Period, these early fish give rise to the first true gnathostomes, fish with well-developed skeletons and true jaws. By the end of the Devonian Period, some of those jawed fish had even begun to crawl onto land.

Bottom left: The Ordovician conodont Archeognathus. Image by Briggs et al 2018, CC BY 3.0

Right: Skull of the early jawed fish Dunkleosteus. Image by Dropzink, CC0

Exactly what made the vertebrate body plan so successful is not totally clear. Many researchers have noted that the shift from early chordates to vertebrates involved a major focus on the head: well-developed gills, expanded sensory organs, a segmented brain, and more. It seems likely that a well-defined head allowed early vertebrates to navigate their environment and find food so efficiently that they were quickly able to diversify and become one of the most numerous groups of animals on Earth.

Learn More

Early vertebrate evolution (technical, open access)

A recent look at Pikaia and the chordate body plan (technical, open access)

A new (2024) early chordate, Nuucichthys (technical, open access)

__

If you enjoyed this topic and want more like it, check out these related episodes:

- Episode 9 – The Cambrian Explosion

- Episode 77 – Fins to Feet: The Fish-Tetrapod Transition

- Episode 89 – The Burgess Shale

- Episode 210 – Bones

We also invite you to follow us on Facebook or Instagram, buy merch at our Zazzle store, join our Discord server, or consider supporting us with a one-time PayPal donation or on Patreon to get bonus recordings and other goodies!

Please feel free to contact us with comments, questions, or topic suggestions, and to rate and review us on Spotify or Apple Podcasts!

Leave a comment