Listen to Episode 37 on PodBean, Spotify, YouTube, or your favorite podcast source!

This episode, our topic is one of the most detailed and exciting stories of evolutionary origin in the fossil record, one of the most historically fascinating questions in paleontology, and the single most requested topic from our listeners: The story of the Evolution of Birds.

In the news:

30,000 years of life – and death – in the Great Barrier Reef.

Researchers investigate why bony fish don’t grow to whale-size anymore.

Say hello to the earliest land-living vertebrates in Africa.

A new look at an old fossil reveals it to be the oldest fossil lizard.

Birds

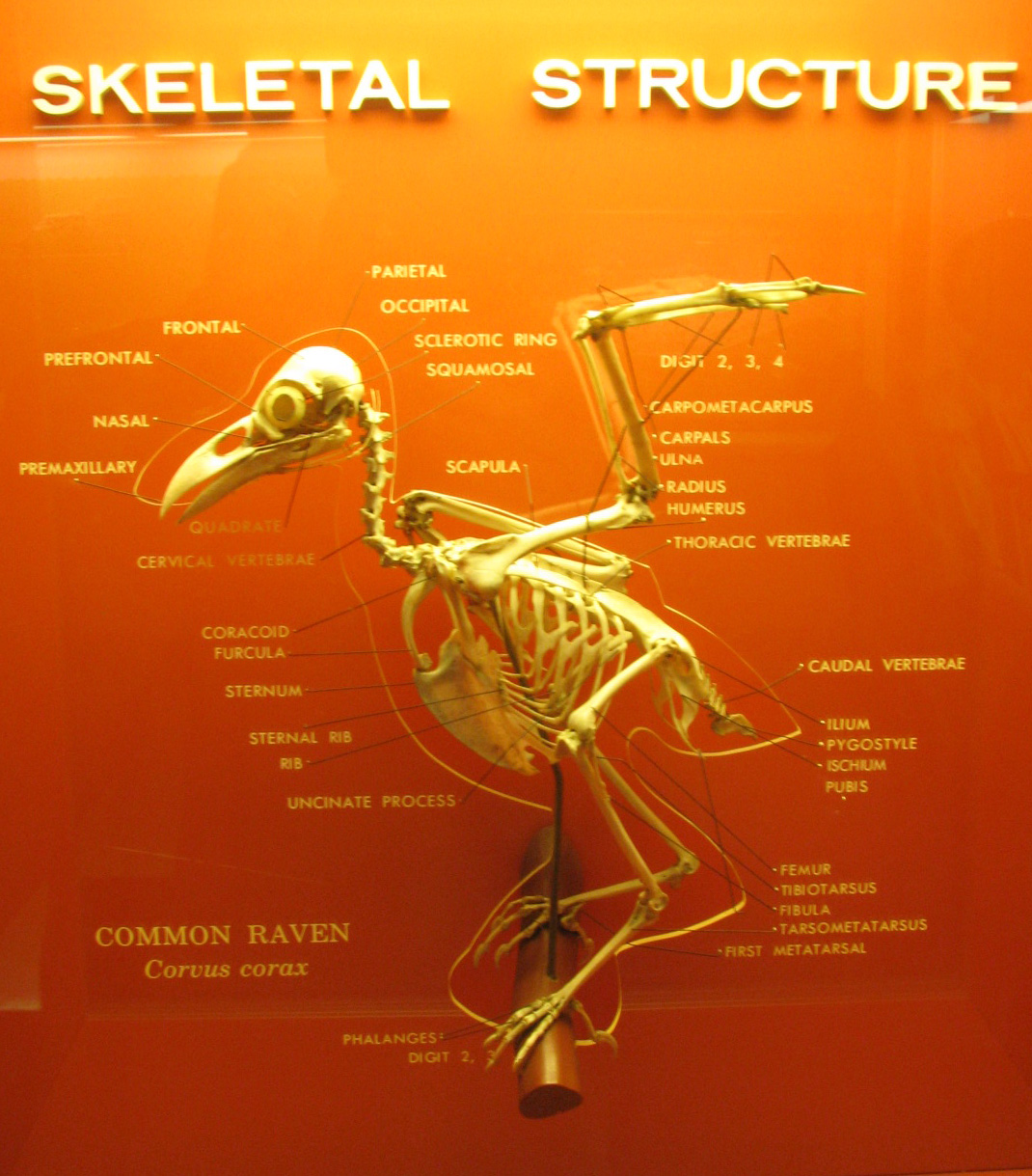

Birds are among the most successful groups of vertebrates in Earth history. There are at least 10,000 species alive today across just about every environment on the planet. They’re also one of the most unique groups, with a long list of features not seen in any other animals. Perhaps that’s why scientists had so much trouble trying to figure out where they fit on the tree of life.

Archaeopteryx and the Origin of Birds

In 1861, the first skeleton of Archaeopteryx became one of the earliest known examples of a “transition fossil” – it had obvious avian features (feathers, wings, three-toed feet, etc) mixed in with very reptilian traits (long tail, teeth, large-clawed hands). Scientists pretty quickly surmised there was an evolutionary link between birds and reptiles.

Some scientists – like Thomas Henry Huxley and Othniel Charles Marsh – correctly linked Archaeopteryx with theropod dinosaurs all the way back in the late 1800s, but not everyone was convinced, and competing hypotheses hung around for decades, most notably the suggestion that birds evolved from much earlier crocodylomorphs or perhaps other early archosaurs.

Over a century after that first Archaeopteryx skeleton, the bird-dinosaur link finally became solid science during the “Dinosaur Renaissance.” On the one hand, in the 1970s, famed paleontologist John Ostrom laid out the clear similarities between Archaeopteryx and dinosaurs such as his then-recently-discovered Deinonychus. On the other, the rise of modern cladistics (check out Episode 10!) allowed paleontologists to statistically confirm the relationships between birds and extinct dinosaurs.

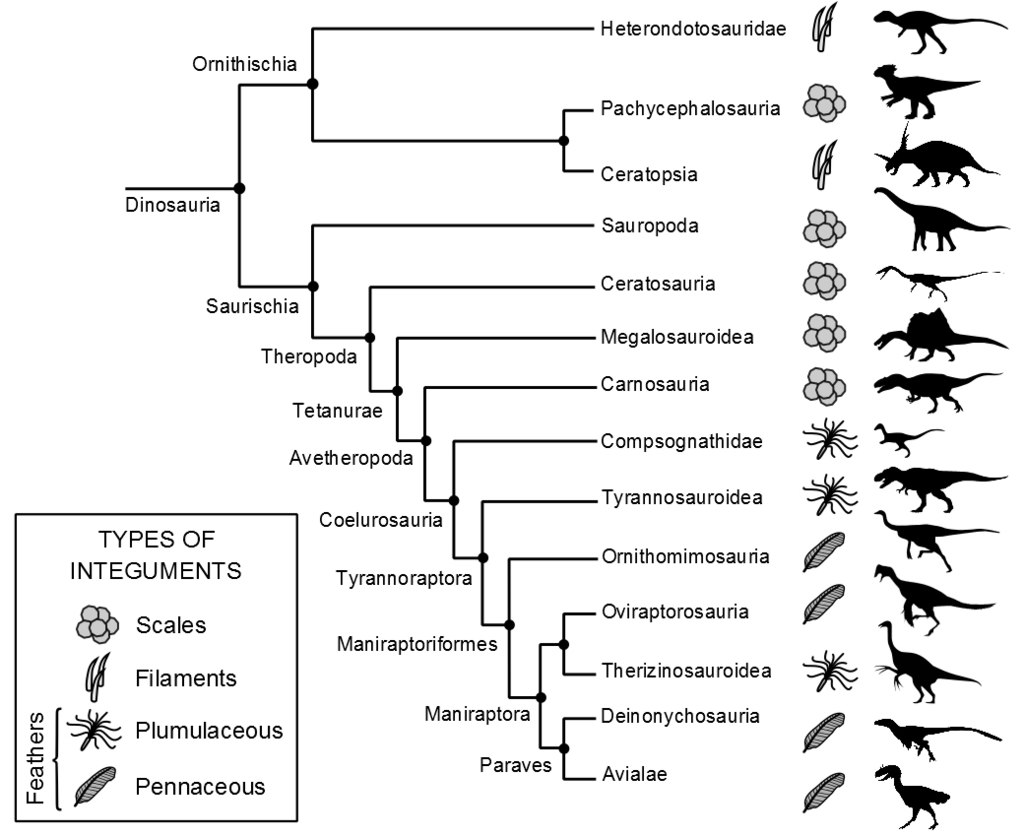

We know now that birds are a subset of dinosaurs! In fact, they’re very closely related to the lineages that include Velociraptor and Troodon.

Feathered Dinosaurs and Toothed Birds

Since the mid-1900s, ever more fossils of prehistoric dinosaurs have given us a much clearer picture of the evolution of bird-like features. Many classic “bird traits” have been found across the dinosaur family tree, including hollow “pneumatic” bones, internal air sacs, powerful arm and chest muscles, specially-fused bones of the limbs and hips, and feathers of all sorts! These are not bird-traits, but dinosaur-traits that birds inherited!

Archaeopteryx shared the Late Jurassic world with a number of animals that appear to be either very early members of the bird lineage or very close relatives, including a bunch of new finds from China: Xiaotingia, Anchiornis, Ostromia, and more! At some point around this time, birds evolved flight (more on that in Episode 6).

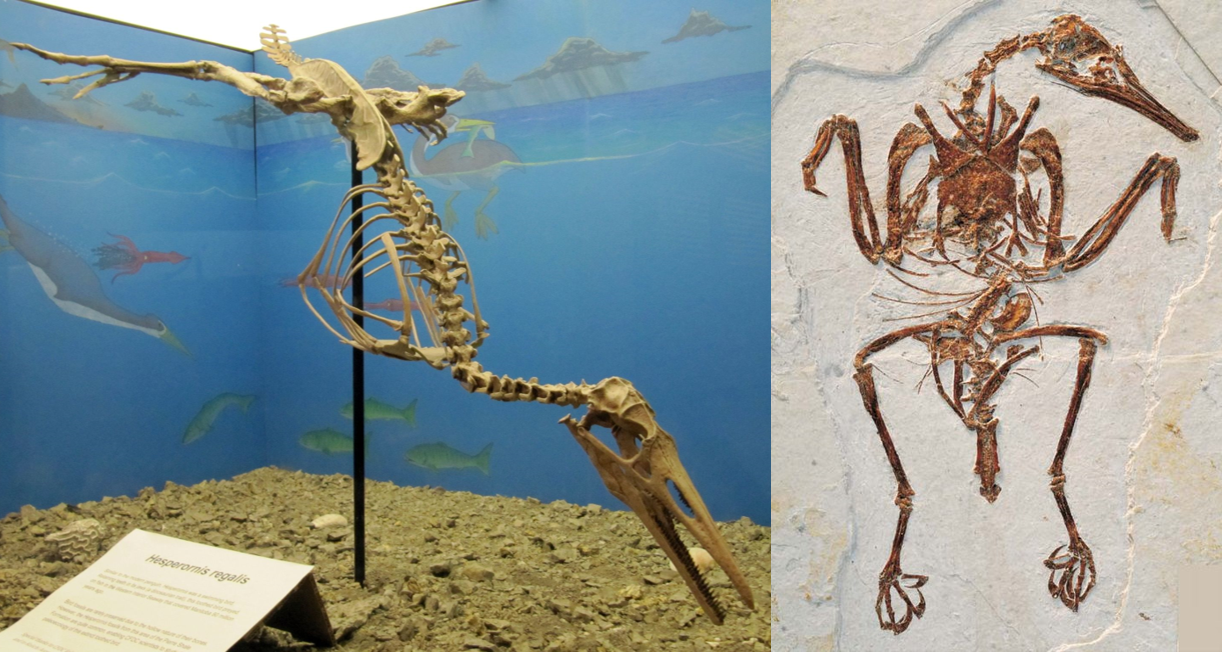

Through the Cretaceous, true birds diversified into an astounding variety, gradually accruing the more familiar features we see in birds today. The famous Chinese Confuciusornis had a tail like a modern bird; the crazy-successful Enantiornithes were very much like modern birds but with teeth and perhaps a different manner of flight; North American Hesperornis was very much like a modern bird (albeit with teeth), but fully adapted for swimming instead of flying!

Truly modern birds had evolved by the end of the Cretaceous, and it was a small group of these that ended up being the sole survivors of the end-Cretaceous mass extinction (see Episode 5) – in fact, the only dinosaurs that made it through at all! From that bottle-necked group of beaked, toothless, very familiar-looking birds, all modern avian groups diversified and conquered the Cenozoic Era.

More Info

Check out Berkeley’s Evolution webpages for more info on the Evolution of Birds and the History of Scientific Thought on the subject.

If you want LOTS more details on ancient birds and bird-relatives, dive into Dr. Thomas Holtz’s excellent course: Dinosaurs, a Natural History.

If you want to learn a ton about modern birds, check out Cornell Ornithology.

But wait, there’s more!

In Episode 37.5, we presented mini-discussions on three specific bird topics, by request: flamingos, terror birds, and history’s largest flying birds. Here’s some info!

Flamingos

Flamingos are unique, stilt-legged wading birds with strange skulls highly adapted for a life of filter-feeding upside down in salty water. The fossil record of flamingos goes back as far as the Eocene, almost 50 million years ago. For many millions of years, modern-style flamingos lived alongside an extinct family of swimming flamingos, the Palaelodidae.

The San Diego Zoo site has lots of great info about living flamingos.

And here’s that news story about flamingos in Florida.

For a non-technical glimpse at the fossil record of flamingos, read about Australian flamingos.

For more technical info: check out Mayr 2004 on flamingo relationships; Worthy et al. 2010 for recent info on the extinct “swimming flamingos;” and Mayr 2005 for an overview of the flamingo fossil record (and lots of other birds).

Terror Birds

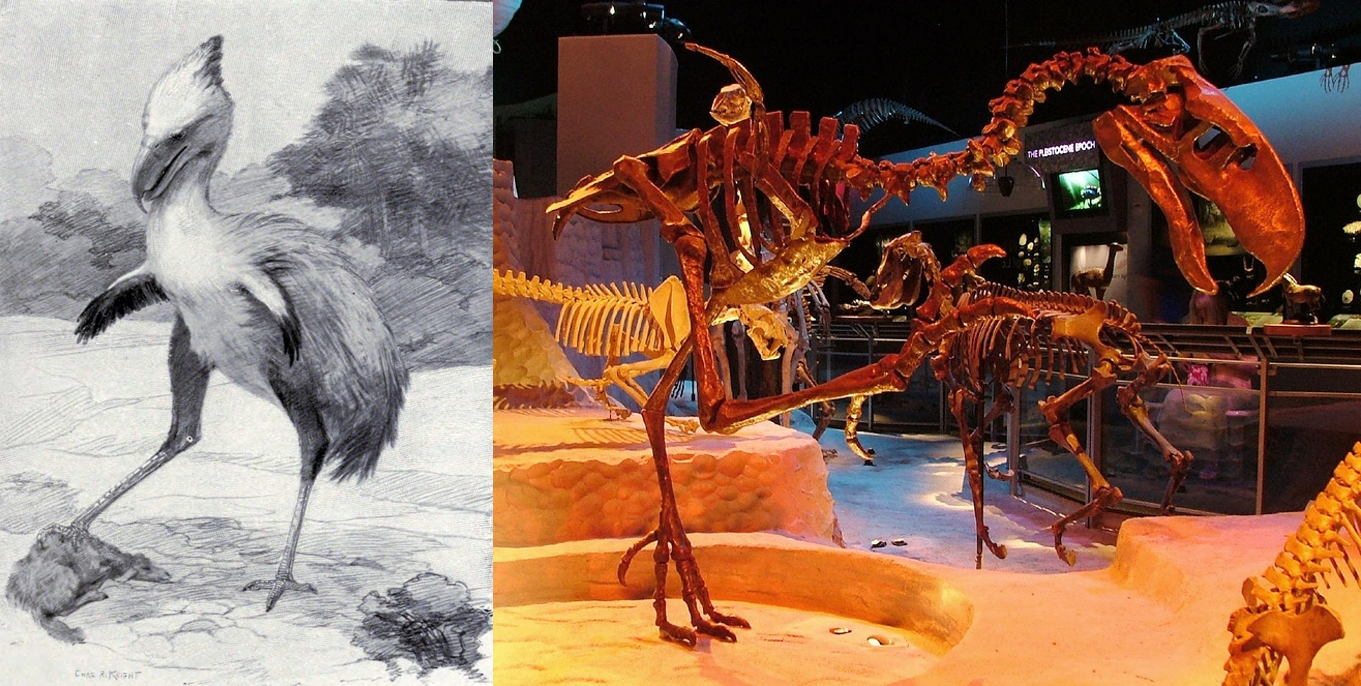

The Phorusrhacidae, commonly – and dramatically – known as the “terror birds,” were a family of flightless predatory birds that lived mainly in South America for much of the past 60 million years. Some of these birds were similar in size (and perhaps habits) to their living cousins, the seriemas, while the most famous of them were gigantic, standing perhaps 3 meters (10 feet) tall with powerful back legs and axe-like beaks.

Our friend Aaron wrote a great overview of this group of birds at Life in the Cenozoic, and there’s yet more info on Letters from Gondwana. There’s also an episode of Eons about the latest terror birds.

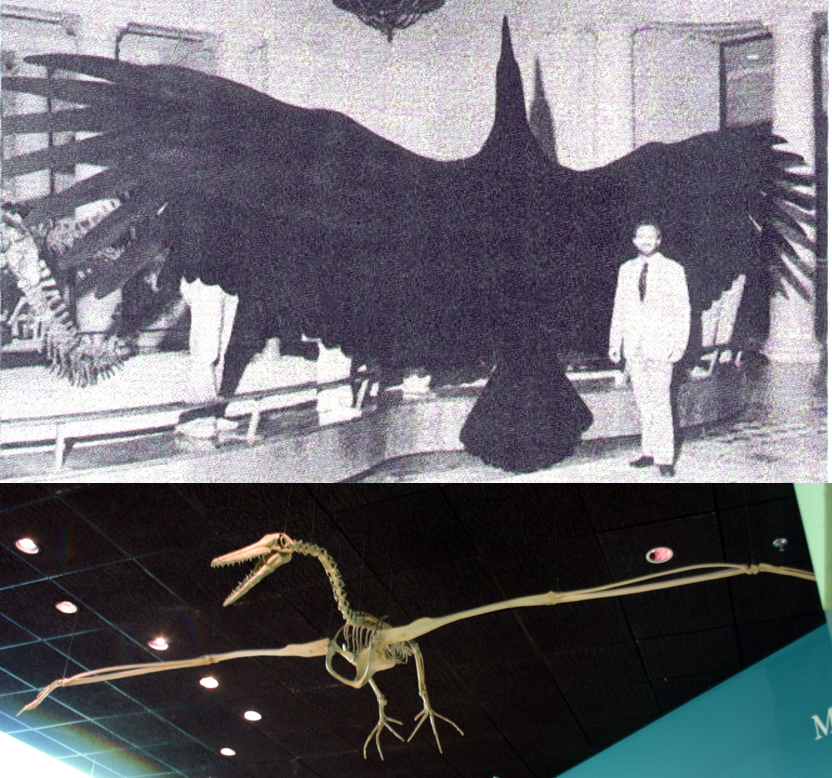

Argentavis and Pelagornis

The largest flying birds today, depending on what you’re measuring, include the Kori bustard, which can weigh nearly 20kg (44lbs), and the wandering albatross, which can have a wingspan up to 3.5 meters (11 feet). Large size can be beneficial for many reasons, and big wings make for great gliding ability, but it can be difficult to get such a large animal into the sky.

Argentavis magnificens lived in South America around 6 million years ago. It was a close relative of condors and New World vultures, and weighed an estimated 70kg (150lbs), with a wingspan as wide as 6.5-7 meters (21-23 feet). Despite its size this bird has all the hallmark adaptations of a frequent flier and probably stayed aloft by riding thermals (rising warm air) or slope winds (wind blowing up mountain slopes) across the foothills of the Andes, similar to modern-day large condors.

Pelagornis sandersi hails from South Carolina, 25 million years ago. It was one of the “pseudo-toothed birds” identified in part by the spiky tooth-like projections coming off of its beak. It had a similar wingspan to Argentavis (6.5-7 meters), but weighed far less, estimated at only 21kg (50lbs). P. sandersi is found in marine sediments, and probably flew on ocean winds like modern-day albatrosses.

For some more technical info: Chatterjee et al 2007 did an analysis of flight in Argentavis, and Ksepka 2014 did a similar study on Pelagornis.

And this YouTube video provides a fun look at how albatrosses use dynamic soaring to stay aloft, and how Pelagornis sandersi might have done the same.

—

If you enjoyed this topic and want more like it, check out these related episodes:

- Episode 6 – Evolution of Flight

- Episode 108 – Penguins

- Episode 139 – Vultures

- Episode 86 – New Zealand

We also invite you to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram, buy merch at our Zazzle store, join our Discord server, or consider supporting us with a one-time PayPal donation or on Patreon to get bonus recordings and other goodies!

Please feel free to contact us with comments, questions, or topic suggestions, and to rate and review us on iTunes!

Guys, you missed a pun at the beginning of ep 37.5: shouldn’t that be “bonus smorgasBIRD”?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Also guys you completely buried the lede with the recommendation of Manly Guys Doing Manly Things because OMG i haven’t gotten to the fluffy pet velociraptors yet but MR FISH.

MR FISH IS A GORRAM STAR.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Awesome to learn about enantiornithes! I had overlooked them before, and so after listening to this episode I did a lot more research on them. Fascinating!

LikeLike