Listen to Episode 43 on PodBean, Spotify, YouTube, or wherever podcasts are sold (just kidding, it’s free!).

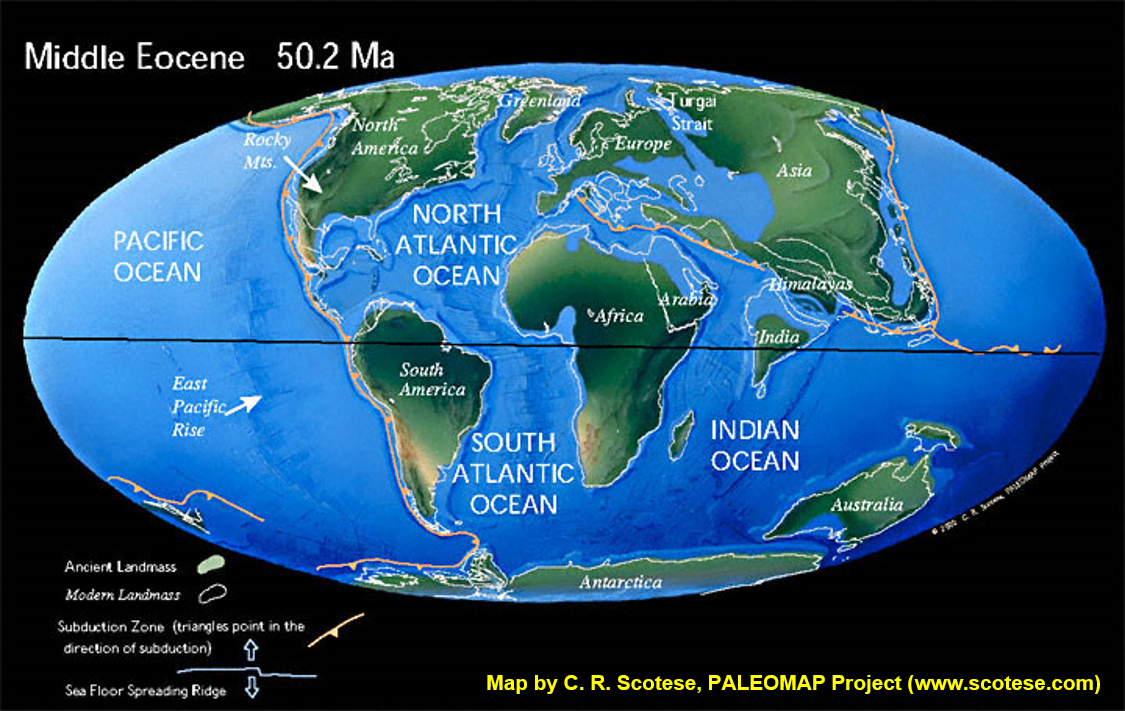

For tens of millions of years, North and South America were separate sisters across the sea, each with their own unique ecosystems. That is, until around 3 million years ago, when tectonic activity birthed the Isthmus of Panama and allowed an incredible mass migration of life across the bridge: The Great American Biotic Interchange.

In the news

Scanning prehistoric fly pupae revealed parasitoid wasps inside!

Meet the newest Triassic turtle ancestor, the beaked Eorhynchochelys.

Assembled teeth track changes in Jurassic marine ecosystems.

DNA reveals a Siberian hominin with a Neanderthal mother and Denisovan father.

The National Museum of Rio de Janeiro has suffered a terrible fire. Many of their collections have been destroyed and we don’t yet know the extent of the damages. This story is still developing, as of this posting.

Cenozoic South America

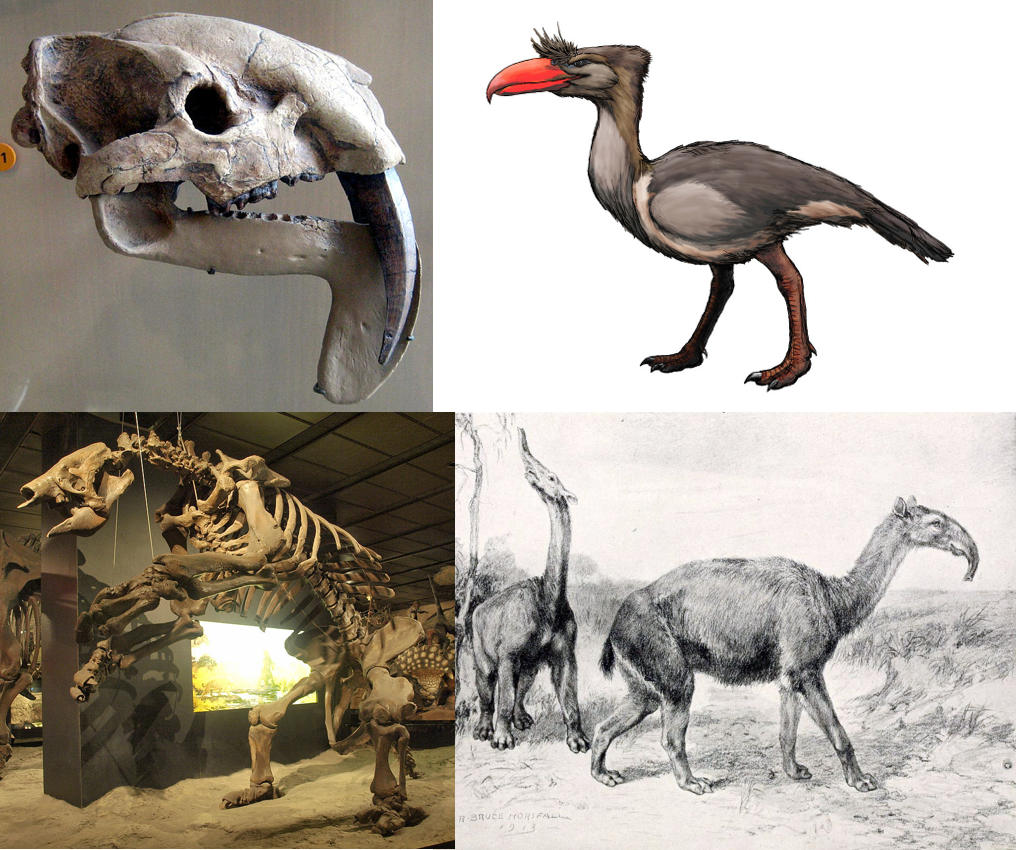

By the early Cenozoic, South America had broken away from all other continents, leaving it isolated, practically an island continent. And as you’ll remember from Episode 4 and Episode 40, life gets weird in isolation. South America became home to all sorts of strange animals: bizarre hoofed mammals, marsupial carnivores, the phorusrhacid “terror birds,” and the always-strange sloths.

There’s a fair bit of debate over when exactly South America started reconnecting with North America. But what’s generally agreed upon is that by the Late Miocene, around 12 million years ago or so, tectonic forces were filling the Central American Seaway with new land. This is evidenced in the fossil record by the appearances of new mammals island-hopping or swimming across the gap: raccoon-cousins in South America and ground sloths in North.

And then, around 3 million years ago, the Isthmus of Panama settled into place, and the doors opened for a mass migration that continues to this day.

North Meets South

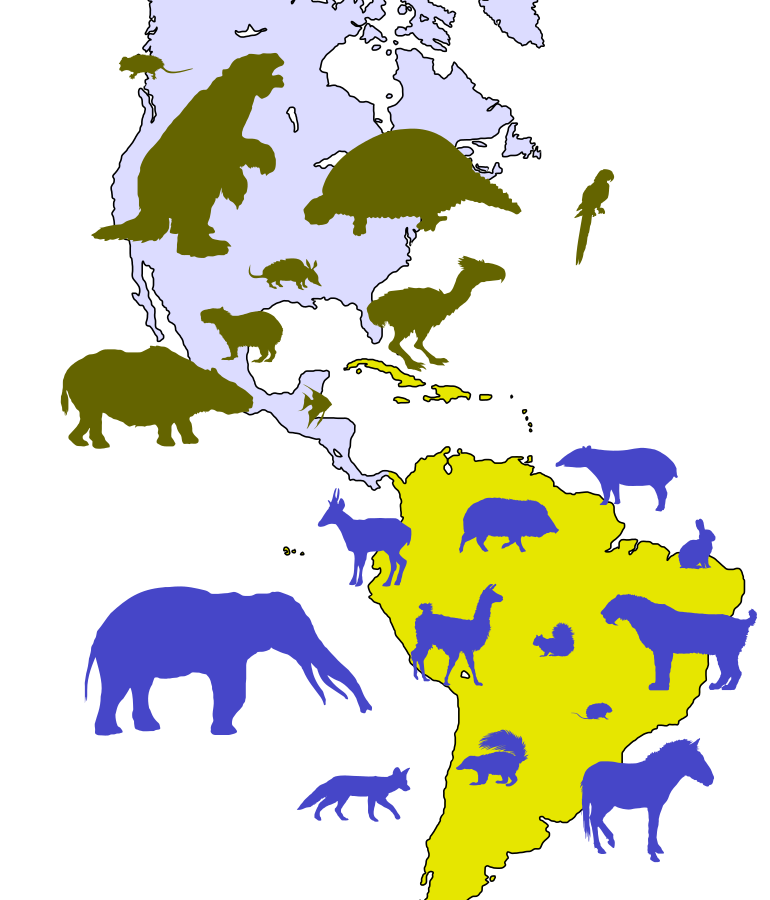

North America received many southern immigrants in the Interchange, including extinct favorites like giant ground sloths, armored glyptodonts, and the terror bird Titanis walleri, as well as some familiar animals still living up north today such as armadillos and opossums.

Meanwhile, South America was inundated by an influx from the north, including felines, canines, bears, camels, tapirs, elephants, and more.

One of the major results of the GABI was a huge change in South American ecosystems. Having evolved in isolation for so long, the southern faunas weren’t quite prepared for the North American groups that had been competing with European, Asian, and African connections for millions of years. Many of South America’s endemic mammals went extinct around the time the GABI began, and many more later. Today, about half of South America’s mammals are descended from northern groups.

Most of our understanding of the GABI comes from mammals, but there are clues that this event spurred an exchange of frogs, snakes, birds, plants, and more!

More Info (mostly technical this time)

Two detailed (technical) overviews of the GABI, which we used for planning this episode, are Woodburne 2010 and Cione et al. 2015.

O’Dea et al. 2016. Formation of the Isthmus of Panama (technical)

Did South America’s animals have to get better protected to deal with northern predators? Zurita et al. 2010 (technical).

Also, for more (non-technical) on how the formation of the isthmus of Panama may have impacted global climate, read here. And this paper for a technical discussion.

—

If you enjoyed this topic and want more like it, check out these related episodes:

We also invite you to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram, buy merch at our Zazzle store, join our Discord server, or consider supporting us with a one-time PayPal donation or on Patreon to get bonus recordings and other goodies!

Please feel free to contact us with comments, questions, or topic suggestions, and to rate and review us on iTunes!

I’d like to request a few topics for an episode or two:

1. Paleoart

2. Pterosaurs

3. More “science reviews” of movies, maybe Pacific Rim, Godzilla (2014), and Kong: Skull Island, as well as any others you could think of.

4. More speculative evolution would be fun.

I love listening to your podcast and it’d be fun to hear about these topics on the Common Descent Podcast sometime!

Thanks!

LikeLike

Hi Ed,

These are great requests! They are all going on the list! Look out for them in the future.

Thanks!

CD

LikeLike

Great podcast. Thoroughly enjoyed it. Just wanted to highlight another significance that this geological event might have had. The formation of the isthmus contributed to development of ice sheets, which in turn locked up a lot of moisture globally. This meant that deserts expanded, while rainforests retreated. In East Africa, the Autralopithecines were slowly adapting to a more open savannah, as the trees were few and far in between. Therefore, the Panama isthmus might have inadvertently triggered our evolutionary development/pathway from tree-dwelling apes to terrestrial bipeds. It may have also helped the expansion of our own species out of Africa via land bridges connecting Africa to Arabia.

Quite fascinating if you think about it. Had that isthmus not formed, would we have still evolved?

LikeLike

Just listened to this episode (found your podcast, doing a binge-listen to get me through the work-days) and my imagination, upon being fed the mental image of a terrorbird and a sabertooth cat meeting, threw back Tweety-Bird’s ‘I tawt I taw a puddy-tat!’ but in a horrible baritone death-metal shriek. ROFL

LikeLike