Listen to Episode 47 on PodBean, Spotify, YouTube, or wherever you find your podcasts.

*Don’t forget to submit your questions for our End Of The Year Q&A!

In today’s world, there is only one group of synapsids: the mammals. But for a good 100 million years before true mammals appeared, a diverse array of non-mammalian synapsids dominated ecosystems on land. In this episode, we’re following the story of synapsid evolution from their earliest lizard-like ancestors right up to the origin of true mammals.

In the news

Surprise! DNA analysis reveals a new living species of crocodile.

A new skull of Pachycephalosaurus has … meat-slicing teeth?

These unusual footprints are the oldest in the Grand Canyon.

Early fish evolution may have been centered unexpectedly on shorelines.

What’s a Synapsid?

The first vertebrates on land were amphibians descended from fish, and during the Carboniferous Period one branch of these amphibians became the amniotes – vertebrates that laid eggs specially built to survive on land. This was kind of a big deal.

Very quickly, the amniotes split in two. One branch, the sauropsids, would ultimately give rise to snakes, crocs, turtles, dinosaurs, ichthyosaurs, and all the other critters we call reptiles. The other branch were the synapsids.

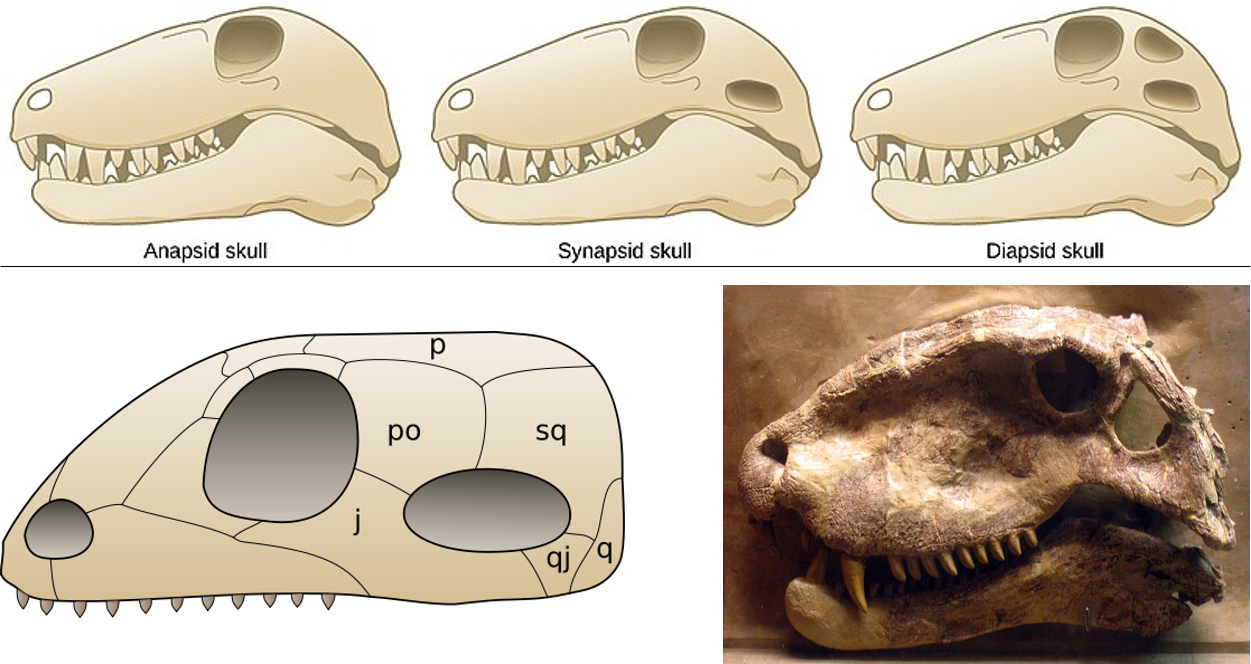

The defining trait of synapsids is the construction of the skull, specifically a lateral temporal fenestra. That is, a hole. On either side of the head, situated between several bones behind the eye socket, this lone fenestra differentiates synapsids from, for example, the two-holed diapsid reptiles.

This simple difference laid the groundwork for the evolution of one of the most successful groups of animals in Earth history.

Let’s meet a few.

Meet The Extended Family

The earliest synapsids in the fossil record come from the Late Carboniferous, just over 300 million years ago. Like other early amniotes, they are small and lizard-like, possibly insectivores. These are animals like Archaeothyris and Echinerpeton.

A note about names: this episode focuses mainly on the non-mammalian synapsids, which have in the past gone by the phrase “mammal-like reptiles.” That term has fallen out of popularity recently because it’s misleading; the early synapsids aren’t really reptiles, though they are reptile-like. You’ll also hear “proto-mammals,” which is a bit better, or “stem mammals” which is the actual scientific term for them.

The Pelycosaurs

Several early branches of the synapsid family tree are collectively called the “pelycosaurs.” Though they started small and same-y, they evolved into a huge variety of carnivores and herbivores of all different shapes and sizes. In the Early Permian Period, they dominated ecosystems on land.

In general, pelycosaurs have sprawling limbs (like reptiles and amphibians) and often prominent canine-like teeth. Many, like the famous Dimetrodon (perhaps the least dinosaur-like animal commonly mistaken for a dinosaur), had dorsal sails – they were the first animals to evolve this feature!

Therapsids

One branch of pelycosaurs ultimately gave rise to the therapsids. As the Permian wore on, these newcomers would take over most of the major niches from their pelycosaur ancestors. Among the therapsids, a new selection of carnivores and herbivores, big and small, took to the scene.

These Permian therapsids aren’t mammals, but they’re a bit closer, standing more erect (like mammals do) and with a greater variety of teeth (also a mammal trait).

Cynodonts

As therapsids live on across the Permian Extinction into the Triassic Period, one lineage develops into the very successful cynodonts. These very mammal-like critters include dog-like carnivores and herbivores with great plant-grinding molars, all competing (ultimately not too well) with the diversifying crocodylimorphs and dinosaurs of the Triassic.

Making Mammals

Mammals are defined by a host of familiar traits: fur, deciduous teeth, etc. They didn’t evolve these features on their own, but inherited them from their early synapsid ancestors. Across early synapsid evolution, we can see the gradual development of these traits. Here are some:

Differentiated teeth. Early synapsids have those cool canine-like teeth, and as time goes on this group of animals gradually develops more tooth variety until we have the familiar combo of incisors, canines, premolars, and molars.

The mammalian jaw. In reptiles and amphibians, the lower jaws are made up of many bones, and the jaw joint is a connection between the quadrate above and the articular bone below. In mammals, the lower jaw is one bone on each side (the dentaries) making a joint with the squamosal bone above, while the quadrate and articular have transitioned into inner ear bones. The gradual shift in these features across synapsid evolution is one of the most iconic transitions in the fossil record.

Erect posture. Mammals have a parasagittal stance – they hold their legs directly beneath their bodies. This trait becomes more pronounced in synapsids as time goes on.

Endothermy. It is very difficult to know when mammalian “warm-bloodedness” appeared, but a bunch of evidence including nasal structures important for respiration, vascularization in the bones, and possible fur in a Permian coprolite suggest that mammalian endothermy was in the works long before true mammals appeared.

Speaking of which, true mammals finally evolve within the cynodonts by the turn of the Triassic-Jurassic, complete with all those wonderful mammal features. Throughout the Mesozoic, several groups of mammals evolved, but of course it wouldn’t be until after the K-Pg extinction that synapsids once again rise to rule the world.

Want More?

Here are some good short overviews of synapsids and stem mammals.

This 2014 dissertation gives a very technical, very detailed overview of pelycosaurs.

And for an even more extensive overview of stem mammal and mammal evolution, look into The Origin and Evolution of Mammals by T. S. Kemp.

—

If you enjoyed this topic and want more like it, check out these related episodes:

- Episode 77 – Fins to Feet: The Fish-Tetrapod Transition

- Episode 45 – The Permian Extinction

- Episode 15 – The end-Triassic Mass Extinction

We also invite you to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram, buy merch at our Zazzle store, join our Discord server, or consider supporting us with a one-time PayPal donation or on Patreon to get bonus recordings and other goodies!

Please feel free to contact us with comments, questions, or topic suggestions, and to rate and review us on iTunes!