Listen to Episode 52 on PodBean, Spotify, YouTube, or anywhere they have podcasts!

The sounds that animals make are a huge part of their behavior and how we recognize them. The sounds that prehistoric animals made, on the other hand, are lost to the past. But perhaps not entirely. There have been a few instances where fossils have given us clues to the noises these animals may have made, allowing paleontologists to reconstruct the Sounds of the Past.

In the news

Newly born insects trapped in amber reveal how they hatched.

How did the gain and loss of flight affect bird brains?

New contenders for the title of earliest known fossil flower.

Ankylosaur nasal passages may have acted as cooling systems.

Did Dinosaurs Roar?

Of course, the first group of animals that come up when we wonder how extinct animals sounded are dinosaurs. Not only are they the largest terrestrial animals to have lived, but they are also unusual compared to the animals we know today. This gives us few parallels to use as examples of what noises they may have made.

The sounds we hear in movies are a lot of fun but probably far from the real thing. In fact, according to research on fossil and modern birds, dinosaurs may have made closed-mouth vocalizations instead of open-mouthed roars and chirps. Some birds are able to sing due to a special structure known as a syrinx, but many make noises by inflating a cavity in the neck to make “booming” sounds with their beak closed. This is similar to the way a gator make its bellowing noise during mating season.

Working off this idea, Dr. Julia Clarke at the University of Texas took the boom of a Eurasian bittern and bellows of crocodilians to simulate what a similar noise might sound like if produced by something the size of T. rex. Listen to it here!

This sound may even have been low enough to produce infrasound.

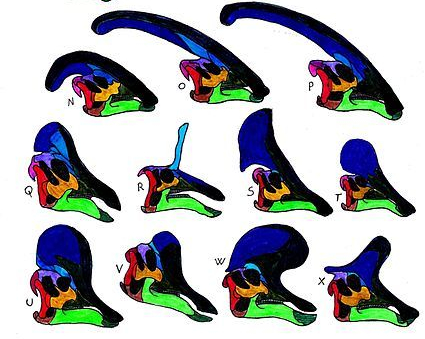

That’s not the only dinosaur whose voice has been reconstructed. The lambeosaurines are a group of hadrosaur dinosaurs famous for their ornate and hollow head crests. When they were first discovered there were many possible answers for the purpose of these crests, including increasing their sense of smell, display, or even that is may have acted as a snorkel. But the hypothesis that gained the most support was that they were for making sound by acting as a resonating chamber.

The most famous of these crests belongs to Parasaurolophus and could measure up to 6 feet long. This dinosaur also had its voice reconstructed by a group of scientists at Sandia National Laboratories, who used the internal shape of its crest to digitally simulate its voice. Listen here!

These were not the only fossil animals thought to make noises with their nose. An ancient wildebeest has been found with a similar schnoz.

Sounds of the Hunters

When it comes to famous animal sounds, the roar of a big cat is close to the top of the list.

There is some evidence that the extinct saber-toothed cat, Smilodon fatalis, may also have been able to roar.

Roaring is an important part of territorial displays and social behavior in modern big cats. Perhaps Smilodon was living similarly?

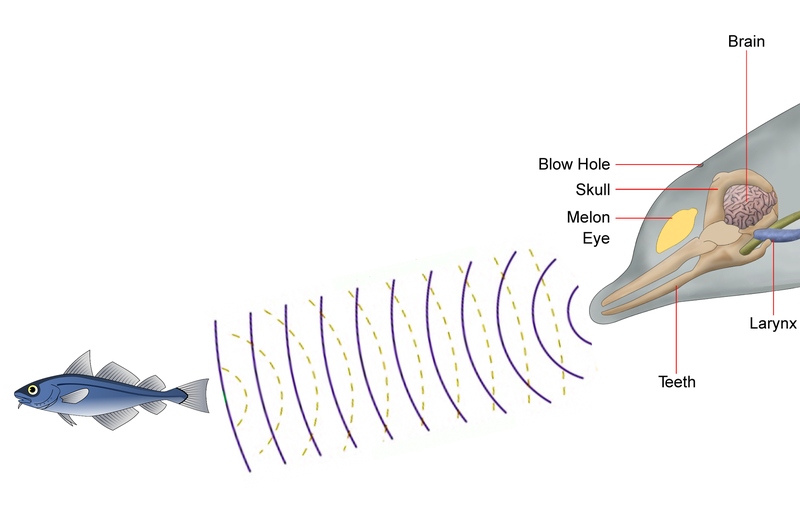

While some predators like to yell, other use sound to hunt. This is known a echolocation and is famous in bats and toothed whales.

The earliest known fossil whale that may have possessed echolocation was Cotylocara macei, living about 28 million years ago. Toothed whales had to develop hearing attuned to ultra-high frequencies in order to create a picture of their environment by listening to the sounds they produced.

Chirping Insects

All of the noises we’ve looked at so far are vocal. But in China, a pair of katydid wings were discovered that still retained the structures used to make their characteristic chirps. Researchers named this katydid Archaboilus musicus, and by examining the microscopically-preserved structure of its wings, they were able to determine what sound it would create, and then they simulated it!

There we hear the sound a single insect made during the Jurassic. This is but one sound out of hundreds that may have filled the air during this time. But its the only one that’s been listened to by human ears.

Other Links

If you’d like to read a bit more about fossil bioacoustics take a look at these link:

How Did Dinosaurs Communicate?

How Dinosaurs Talk With Their Feathers

These are the animal audios we used during the episode:

Great Bittern (Botaurus stellaris) Roger Charters/Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML202485) https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/202485

American Alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) George B. Reynard/Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML163792) https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/163792

Parasaurolophus sound bite by Sandia National Laboratories and the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science with Paleontologist Tom Williamson and computer scientist Carl Diegert https://www.sandia.gov/media/dinosaur.htm

Katydid Stridulation from Jun-Jie Gu et al 2012. Wing stridulation in a Jurassic katydid (Insecta, Orthoptera) produced low-pitched musical calls to attract females, PNAS (Open access) https://www.pnas.org/content/early/2012/02/02/1118372109

—

If you enjoyed this topic and want more like it, check out these related episodes:

- Episode 61 – Behavior in the Fossil Record

- Episode 68 – Evolution of Eyes

- Episode 130 – Sense of Smell

We also invite you to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram, buy merch at our Zazzle store, join our Discord server, or consider supporting us with a one-time PayPal donation or on Patreon to get bonus recordings and other goodies!

Please feel free to contact us with comments, questions, or topic suggestions, and to rate and review us on iTunes!

If you two could do some of these requests as episodes or mini episodes (like 37.5) that would be great! Here we go:

Pterosaurs.

The “fish-amphibian” transition, tetrapodomorphs.

The “amphibian-reptile” transition and the amniotic egg.

Genetics in evolution.

Turtles!

More dinosaur episodes.

A 37.5 style episode of weird Triassic reptiles.

Thank you!

LikeLike

Hi Austin. Thanks for the suggestions! We’ll add them onto the list!

LikeLike