Listen to Episode 72 on PodBean, Spotify, YouTube, or that other podcast place you like!

We’re no strangers to fascinating marine creatures on this podcast; we’ve tackled placoderms, whales, sharks, and mosasaurs. But weirder perhaps than all of those were a group of Mesozoic reptiles with large flippers, tiny tails, and heads that ranged from giant death traps to tiny noggins atop long necks. This episode, we dive into the Plesiosaurs.

In the news

Did sauropods have beaks?

A long history of croc snouts and diets.

Investigating the death of the last mammoths on Earth.

Hundreds of new tardigrade-like animals discovered in amber.

Plesiosauria

The first recognized specimen of a plesiosaur was discovered by Mary Anning in 1823, and it became known as Plesiosaurus. We now know that plesiosaurs were extremely diverse and globally distributed throughout both freshwater and marine environments of the Mesozoic.

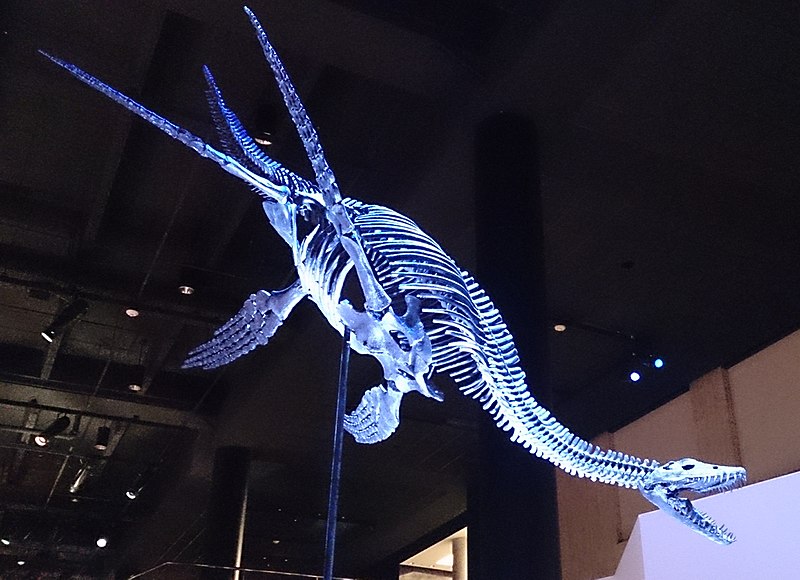

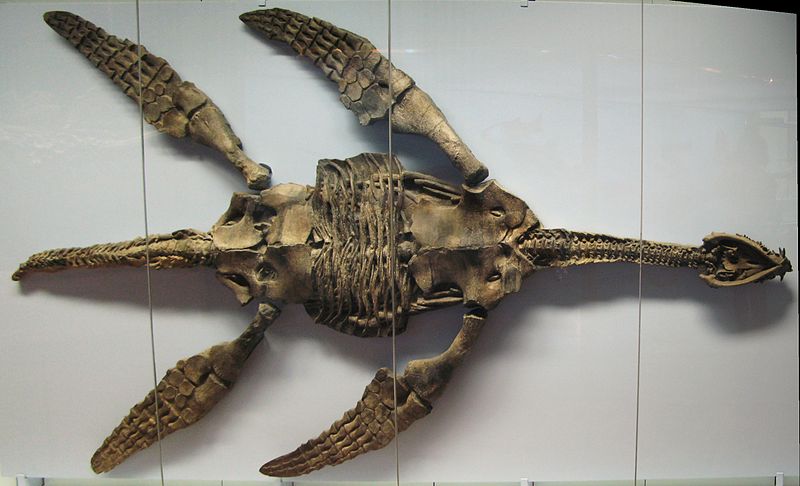

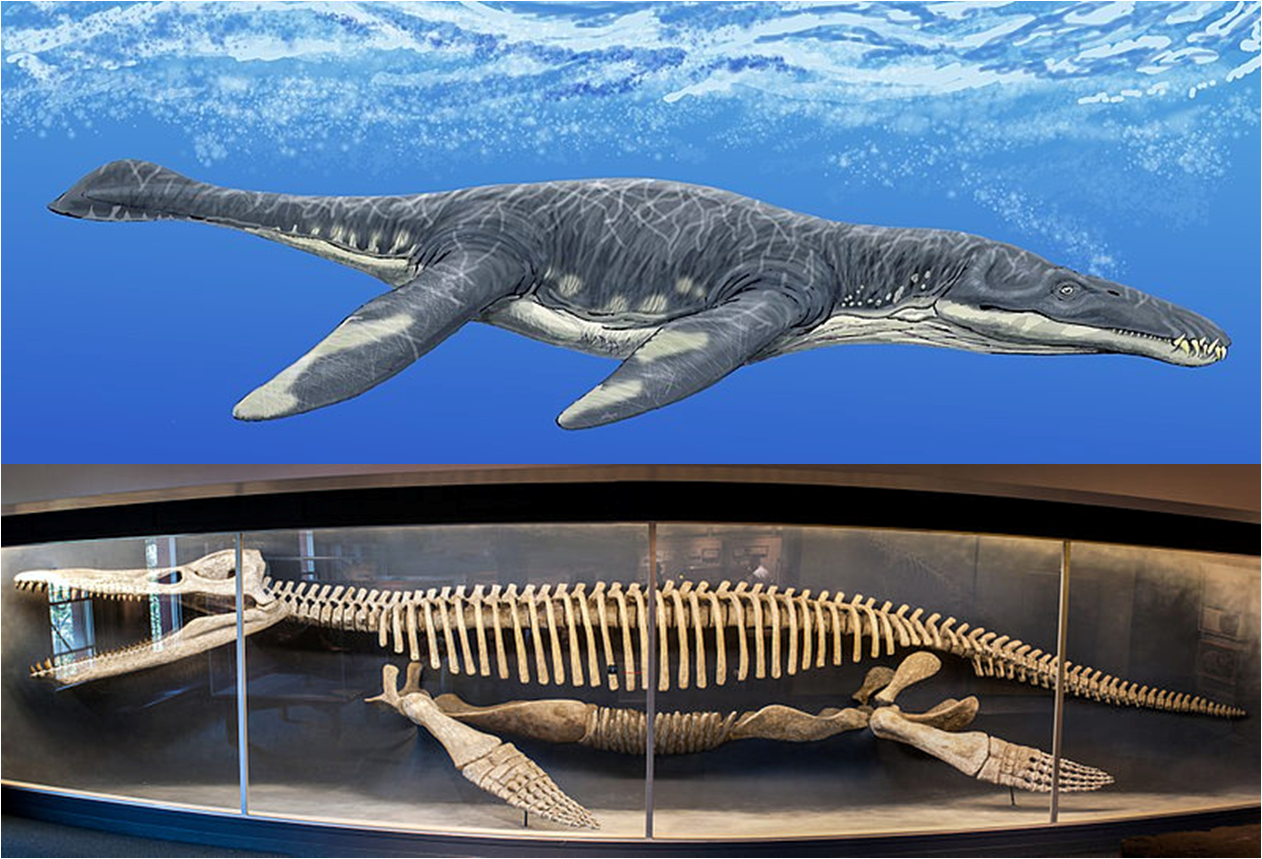

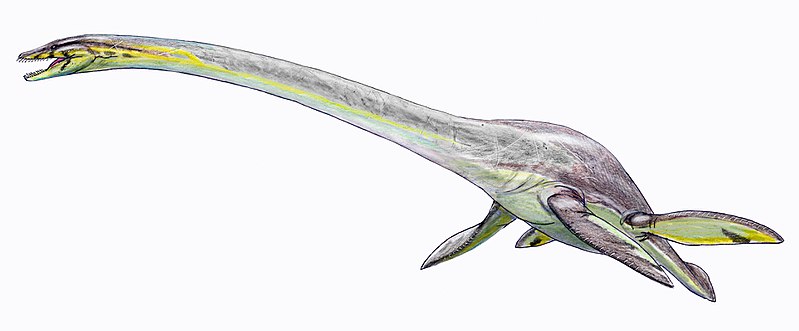

Plesiosaurs are notable for a unique and somewhat bizarre set of features. Their bodies were short and stiffened and their tails were very short and likely not used for propulsion through the water, although there is evidence that some species may have had a small tail fin. They propelled themselves using four large flippers; since no living animals have quite the same arrangement, there have been many attempts to try to deduce exactly how they were using them, including the design of a plesiosaur robot!

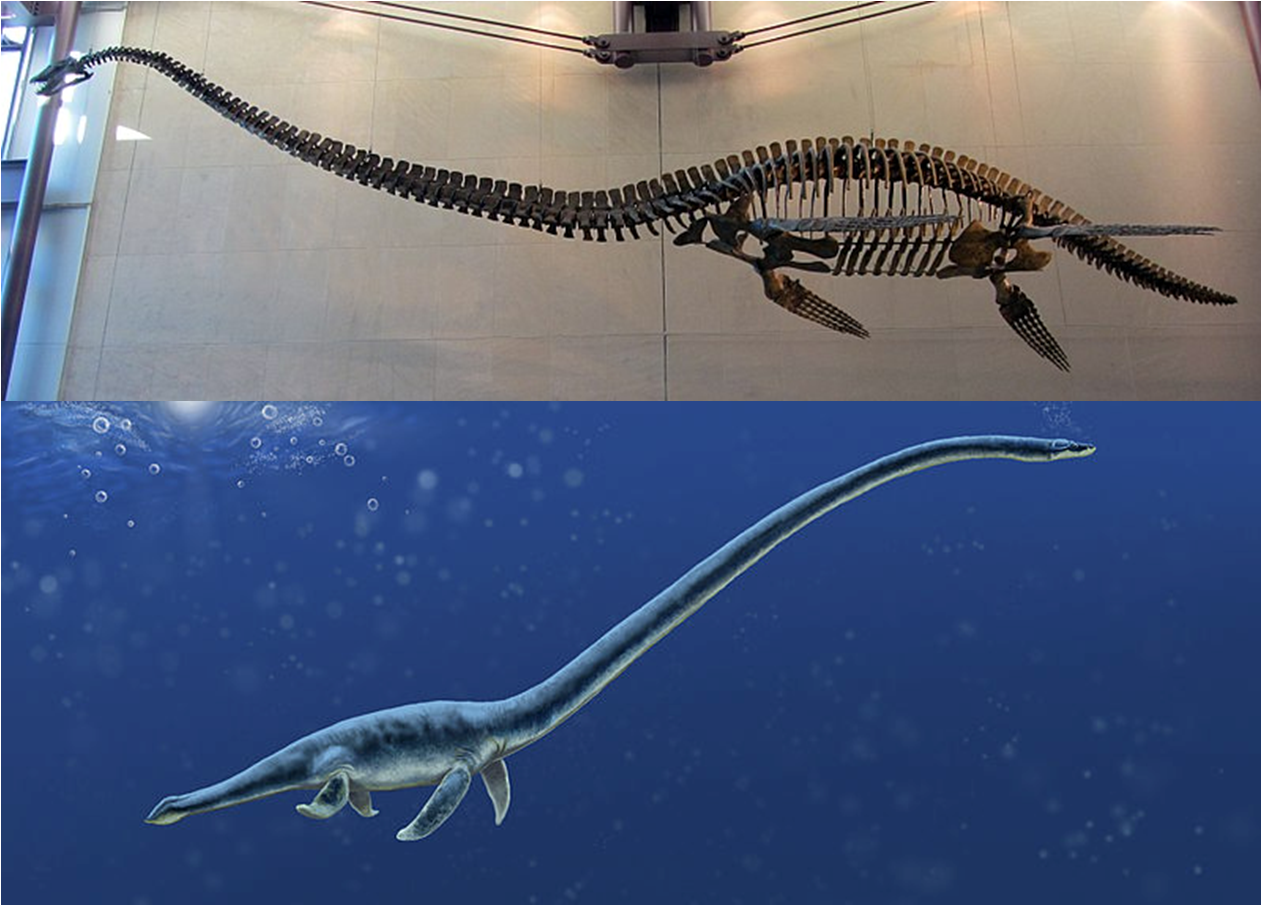

Inside their mouths, plesiosaurs generally had long peg-like teeth, and it appears they were all carnivorous, though their feeding styles varied. Their heads and necks come in two major forms: small heads sitting at the end of long thin necks in the “plesiosauromorphs” and massive, long-jawed heads on very short necks in the “pliosauromorphs.” In the past, these two groups were thought to be different types of plesiosaurs, but now research shows that both long and short necked forms have evolved multiple times.

A History of Plesiosaurs

The first plesiosaurs appeared at the end of the Triassic as part of a diverse group of marine reptiles known as the sauropterygians. These also included pachypleurosaurs, nothasaurs, and pistosaurs, some of whcih were the largest marine predators of the time. Then, at the end of the Triassic, the sauropterygians disappeared almost entirely; the one surviving group was the plesiosaurs.

Exactly why plesiosaurs outlived their relatives isn’t totally clear, though it may have had to do with the fact that they were open ocean swimmers, while the other sauropterygians were coastal. At least some plesiosaurs also gave live birth, which may have given them an extra leg up.

As plesiosaurs continued to diversify, massive “pliosauromorphs” became apex predators with skulls that could reach six feet (two meters) long and and produce a powerful bite.

On the other hand, “plesiosauromorphs” appear to have been eating smalelr fish and invertebrates, though they, too, reached impressively huge sizes.

Exaclty how they used those extremely long necks is a bit of a mystery. Early interpretations imagined them with flexible snake-like necks that they might have used to strike at fish, but more recent research has shown their necks to be fairly stiff and inflexible and probably not capable of much up-and-down motion.

More modern hypotheses include: using their long necks to stretch their small heads unnoticed into groups of fish; reaching into small spaces for prey; extending their reach as they swept their heads around for food; or as a display feature.

Other links

Plesiosaur Peril — the lifestyles and behaviours of ancient marine reptiles

It’s all in the ears: Inner ears of extinct sea monsters mirror those of today’s animals

Sticking your neck out: How did plesiosaurs swim with such long necks?

A new polycotylid plesiosaur with extensive soft tissue preservation

Filter feeding plesiosaur

Fossil ‘sea monster’ found in Antarctica was the heaviest of its kind

“Pliosauromorphs” may have had surprisingly sensitive snout

Functional anatomy and feeding biomechanics of a giant Upper Jurassic pliosaur (technical)

The nothosaur Pachypleurosaurus and the origin of plesiosaurs (technical)

A Plesiosaur Containing an Ichthyosaur Embryo as Stomach Contents (technical)

—

If you enjoyed this topic and want more like it, check out these related episodes:

- Episode 116 – Ichthyosaurs

- Episode 51 – Mosasaurs

- Episode 60 – Turtles

- Episode 71 – The Western Interior Seaway

We also invite you to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram, buy merch at our Zazzle store, join our Discord server, or consider supporting us with a one-time PayPal donation or on Patreon to get bonus recordings and other goodies!

Please feel free to contact us with comments, questions, or topic suggestions, and to rate and review us on iTunes!

Can you please do a podcast episode on basilasaurus! They dont get enough air play in my opinion! Love you guys!

LikeLike

Basilosaurus is awesome! We gave it some attention in Episode 41, but we’ll put it on the list and maybe take a closer look at it sometime!

LikeLike

Can you guys please do a podcast episode on Basilasaurus? They don’t get enough exposure imo! You guys are great!

LikeLike