Listen to Episode 79 on PodBean, Spotify, YouTube, or wherever you find your favorite podcasts!

Around the same time that the first dinosaurs were walking around, another group of reptiles was doing something no vertebrates had ever done before: taking flight. For more than 150 million years, they ruled the skies, and we’ve spent the last 200 years or so learning ever more about just how bizarre and fascinating they were. This episode, we talk Pterosaurs.

In the news

New and surprising data on the evolution of cassowaries

The oldest known scorpion and clues to the earliest animals on land

A taphonomy experiment: alligators on the sea floor

Tools made of shells suggest Neanderthals went diving for resources

The first vertebrate flyers

Pterosaurs first took to the sky in the Late Triassic, at least 225 million years ago. That’s a good 70 million years before birds and 125 million years before bats. They are the first vertebrates to evolve flight (of course, insects beat them by at least 100 million years, but this episode isn’t about insects).

Pterosaurs are generally thought to be close cousins of dinosaurs, although their origins are a mystery. Like bats, the earliest known pterosaurs in the fossil record are already true pterosaurs, with no transitional forms yet discovered to hint at how they took to the air. But once they did, they were extremely successful, filling the skies worldwide for most of the Mesozoic Era, until their extinction at the end of the Cretaceous.

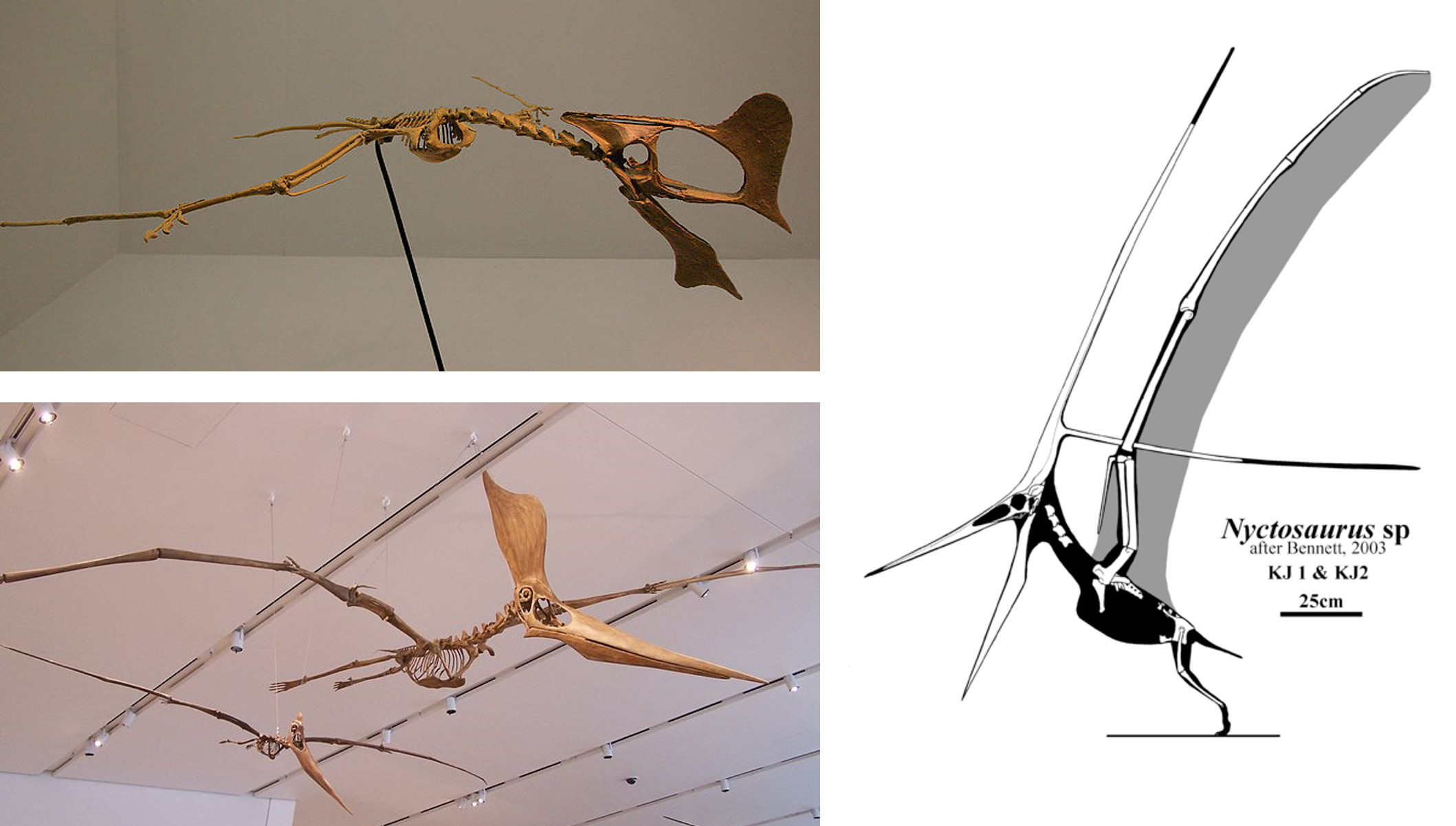

Anatomically, pterosaurs are bizarre. Their front arms and shoulder girdles are enormous to support their wings, and they often have long necks and heads and relatively small hind legs. Like birds, their bones are hollow, very thin-walled, and infiltrated by a series of air sacs that keep their bodies lightweight and aid with their efficient respiratory system

They’re also fuzzy! Many pterosaur fossils have been found covered with bristle-like integument called pycnofibers. A study in 2019 found evidence that pycnofibers might be evolutionarily related to feathers, which would suggest a feathery coat is a very ancient feature for the lineage that gave rise to pterosaurs and dinosaurs.

Endless forms most beautiful

Pterosaurs of the Triassic and Jurassic mostly fall into a group called the “non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs” (formerly called “rhamphorhynchoids”). These were generally small, with wingspans under two meters (6 feet) and sometimes much smaller. Most had long tails, short necks, and large uropatagia between their legs.

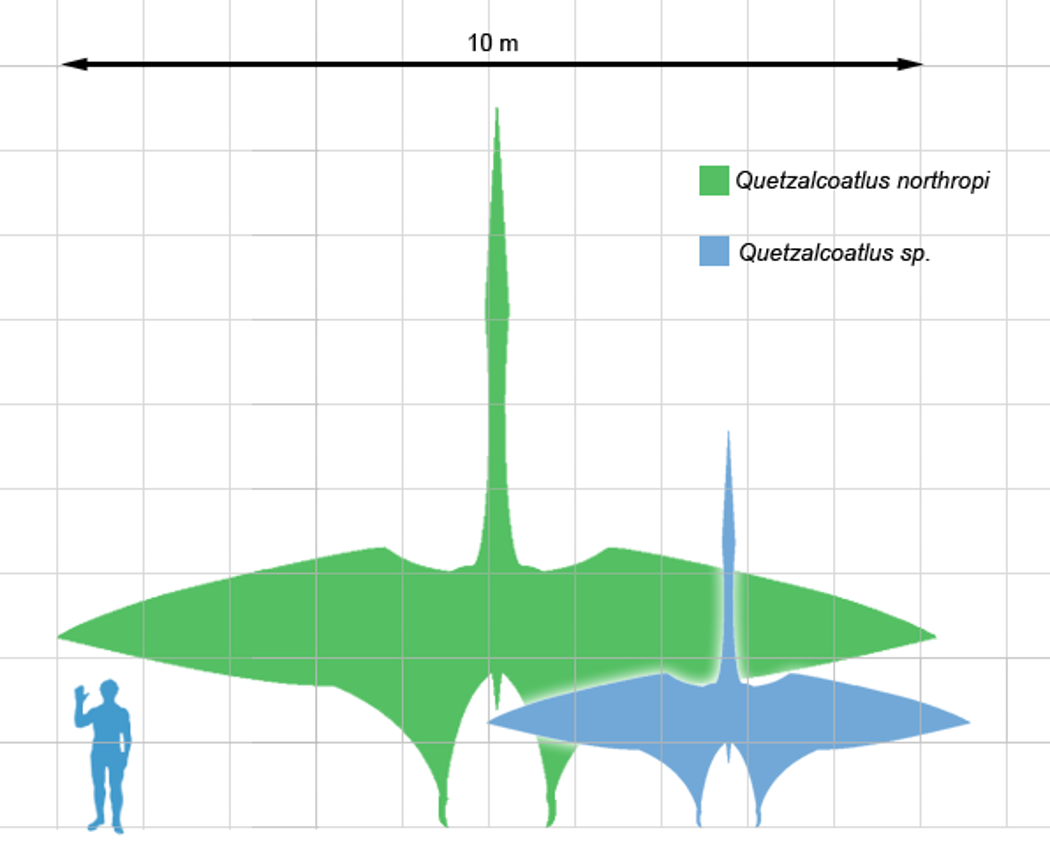

From the Late Jurassic through the Cretaceous, pterosaur diversity was dominated by another group, the pterodactyloid pterosaurs. These were generally short-tailed, long-necked forms. Many were toothless, many had bizarre headcrests, and at the very end of the Cretaceous, a handful grew preposterously large.

From some amazing trackways, we know that pterodactyloid pterosaurs were adept on the ground, walking on their hands and feet with their wings folded. For a long time, no trackways were known to clue us in on early pterosaur walking habits, but that changed this month with a new discovery of Late Jurassic trackways!

A lot of research has gone into the question of how pterosaurs took to the skies. Inspired by modern-day bats, scientists have suggested that pterosaurs used a “quad launch” to get off the ground, using their enormous arms to do a take-off push-up. Here’s a video!

Some pterosaurs even appear to have maintained nesting colonies on the ground!

Images by Mark Witton [CC BY-SA 4.0]; Dmitry Bogdanov [CC BY-3.0]; Jaime A. Headden (User:Qilong) [CC BY 3.0]; and H. Zell [CC BY-SA 3.0]

Learn more

Pterosaur.net is a great resource with lots of general information about pterosaurs.

Mark Witton’s blog is another great place for scientific discussion on pterosaurs. Here are a few blog posts that we used as reference for this episode:

Why we think giant pterosaurs could fly

The life aquatic with flying reptiles

Quetzalcoatlus: the media concept vs. the science

Some technical papers on pterosaur lifestyles:

Bestwick et al. 2018 provides an overview of what we know – and think we know – about pterosaur diets.

Prondvai et al 2012. Life history of Rhamphorhynchus.

Zhou et al. 2017. Coprolites of filter-feeding pterosaurs

Mazin & Pouech 2020. The first non-pterodactyloid pterosaur trackways

With the release of this episode, we donated our December 2019 Patreon earnings to WIRES to help with wildlife recovery during Australia’s current environmental crisis.

—

If you enjoyed this topic and want more like it, check out these related episodes:

- Episode 6 – Evolution of Flight

- Episode 37 – Evolution of Birds

- Episode 59 – Bats

- Episode 99 – Evolution of Insects

We also invite you to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram, buy merch at our Zazzle store, join our Discord server, or consider supporting us with a one-time PayPal donation or on Patreon to get bonus recordings and other goodies!

Please feel free to contact us with comments, questions, or topic suggestions, and to rate and review us on iTunes!

Just looking the video you linked to (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CRk_OV2cDkk), I’ve got to ask is there any fossil evidence for pterosaurs using tendons to store energy for their catapult launch? The type of collagen making up tendons and ligaments is quite efficient at storing energy. It looks like (from the video) that launch requires their legs and wings to move beyond the range of motion they use in flight; using the tendons as springs, not just bone-muscle connections may provide some extra “oomph” when getting off the ground.

A second question is since flight is energetically quite expensive, is there any fossil evidence for pterosaurs losing flight, and becoming strictly terrestrial?

LikeLike

Good questions. We’re not sure about tendons storing energy. It sounds familiar, so we might have read a hypothesis about that, but we don’t have any references for it.

As for flightlessness, it’s intriguing that there is no solid evidence for strictly terrestrial pterosaurs. It has been proposed in the past for the largest species, but mainly based on the outdated idea that they were too big to fly. It would be surprising if no pterosaurs ever lost flight (since birds and insects have done it so often), but there’s no solid evidence yet!

LikeLike

On the topic of flightless pterasaurs, since they launch and move like bats, I wonder if the pressure to lose flight isn’t nearly as strong as it is for insects and birds? Do we have any evidence of bats actually losing flight? I think the closest are the new zealand bats and the vampire bat, but they obviously didn’t lose flight. Maybe it has something to do with using the same muscles for walking and flight that make it less costly to retain the ability to fly, even in an ungainly manner?

LikeLike

A very good point. To our knowledge, there are no known flightless bats either. It could very well be that there’s something about that body plan that makes flightlessness either more difficult or less beneficial. You could be right – bat and pterosaur arms do just fine at both walking and flying, so maybe there’s no strong pressure to give one up.

LikeLike

Thanks!

As a recovering aeronautical engineer (I now teach high school physics), those large, ornate head crests were severely destabilizing and would have significantly increased the energy required for flight, both because of their size (more surface area means more drag) and because of the musculature needed to control head location to maintain stable flight, even disregarding their weight (to quantify that, one would need a high end cfd program). I’ll wager a cup of coffee that those crests are for sexual display (if I ever show up at your workplace I’ll either pay up or collect ;))

Staying in my engineer-in-recovery mode, that long, single finger bone supporting the bulk of the wing seems somewhat vulnerable. Given that some large pterosaurs may have spent a lot of time walking around, being “terrestrial stalkers,” it’s possible for them to have been able to continue eating after that longest of bones was damaged. Knowing that pterosaurs don’t fossilize well, how likely is it that there be, lurking in stone or in a museum closet, one of those finger bones with a healed fracture?

LikeLike

Another good question. We don’t know of any healed wing bones in pterosaurs, though mechanical studies have found their wing bones to be particularly resistant to stress. It’s not hard to imagine a large pterosaur with a broken wing doing just fine on the ground finding food, though it might have missed out on important social behaviors like mating or migrating.

LikeLike

Thank you for creating such an informative, engaging podcast! Could you possibly do an episode on Georg Wilhelm Steller and the Steller’s sea cow, or sirenians in general?

I commend your selfless act in donating to WIRES. Your podcast is one of the main reasons I have gained a greater appreciation for the natural world and our place in it. I hope you are aware that you’re inspiring people to learn about and protect the weird and wonderful wildlife of our planet.

Thanks again!

Austin

LikeLike

Hi Austin,

Good suggestions! We’ll add to the list!

Thanks for your kind words. We’re thrilled to hear we’ve helped inspire you.

David & Will

LikeLike