Listen to Episode 94 on PodBean, Spotify, YouTube, or just search for it in your podcast app!

For tens of millions of years, they were dominant predators in North America, and they have since spread naturally into habitats around the globe, but you know them best as the most iconic domesticated species on Earth. This episode, we explore the diversity, evolution, and history of Dogs.

In the news

Cretaceous “hell ant” caught with prey in its bizarre jaws

New insights on the habits of the bizarre long-necked reptile Tanystropheus

Osteosarcoma in Centrosaurus: the most definitive case of dinosaur cancer

New info on the lifestyle of “super croc” Deinosuchus

Dogs!

Across bottom: Maned wolf, Bush dog, Bat-eared fox, Island fox

Image modified from Wikimedia commons CC BY-SA 3.0

The family Canidae (dogs and their wild cousins) are members of the mammalian order Carnivora. Specifically, they fall within Caniformia alongside bears, weasels, seals, raccoons, and more. Within Canidae, there are three subfamilies: the extinct Hesperocyoninae and Borophaginae, and the living Caninae.

Canids are naturally found on all continents except Australia and Antarctica. They include about 36 species in the 12 genera, Cuon, Nyctereutes, Vulpes, Cerdocyon, Lycalopex, Urocyon, Otocyon, Lycaon, Atelocynus, Chrysocyon, Speothos, Canis. Most living species belong to Vulpes, including all the “true” foxes, and Canis, which includes coyote, wolves, jackals, domestic dogs, and red wolves (though red wolves’ species status is debated. Dogs range in size from the Fennec Fox at 1–1.9 kg (2.2–4.2 lb) up to the Gray Wolf at 14-65 kg (31-143 lb).

Image: Max Hilzheimer, John C. Merriam, Edward Alphonso Goldman and Smallette / Public domain

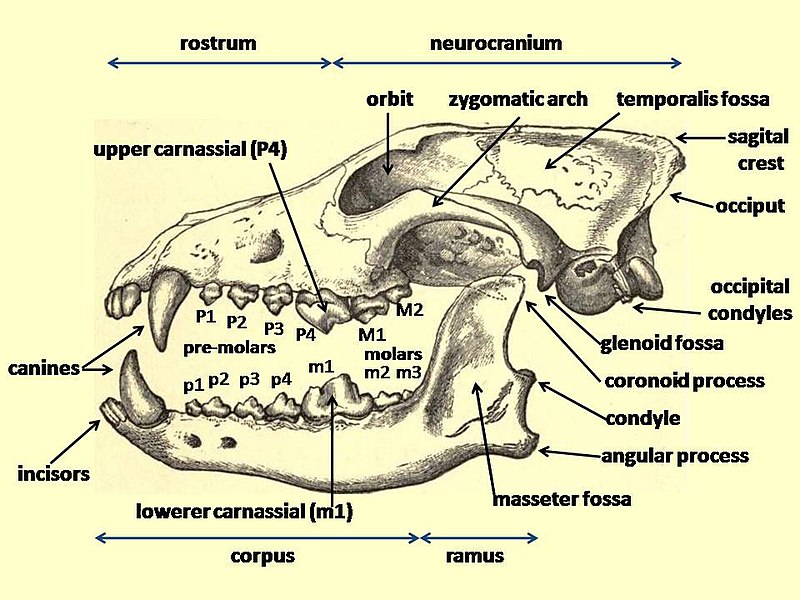

Generally speaking, canids are specialized runners, with long slender legs, forward facing claws, and high stamina. Many species are highly social and may work together to take down large prey. They’re also known for their extraordinary sense of smell. Compared with cats, dogs have lots of teeth with a variety of shapes for slicing or crushing, allowing for a broader diet; only a few canids are considered hypercarnivorous like cats.

Image: William Harris / CC BY-SA 4.0

Fossil Canids

Among the earliest Carnivorans was a small weasel-like predator named Miacis, which lived around 50 million years ago and was likely a tree-climber. By the Late Eocene, around 40 million years ago, the first true canids had appeared, including Prohesperocyon, a small running-adapted animal from Texas. After that came the fox-sized Hesperocyon and ultimately the first canid subfamily, Hesperocyoninae. Though these were true canids, hesperocyonines were more raccoon- or civet-shaped, with relatively short limbs and flexible bodies.

In these early days, and for most of their evolutionary history, canids were restricted to North America.

Image: Daderot / CC0

The next subfamily to evolve were Boraphaginae, the so-called “bone-crushing dogs.” Like modern dogs, these were pursuit predators that may have even hunted in packs. The largest of these, Epicyon, could grow to the size of a large bear, making it the largest known canid.

Left image: Ryan Somma / CC BY-SA 2.0

Right image: Jay Matternes. / CC BY-SA 4.0

As their name implies, borophagines had teeth and jaws adapted for delivering a powerful bite for crushing bone, not unlike hyenas. This is supported by the discovery of borophagine coprolites filled with bone shards.

Finally, by the Early Miocene, around 25 million years ago, Caninae had evolved – true canids. Among the earliest (and smallest) was Leptocyon, followed by Eucyon. Eventually, these early forms would give rise to the modern genus Canis, by around 6 million years ago.

It’s also around this time that canids finally make their way out of North America, spreading into new habitats in Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America.

In the last couple million years, during the Ice Age, many canid groups diminished, but one famous species, the dire wolves, flourished and directly competed with big saber-toothed cats like Smilodon.

Image: James St. John / CC BY 2.0

Not Quite Dogs

Throughout the Cenozoic Era, there have been a number of mammal groups that have convergently evolved very dog-like forms despite not being true canids. These include the so-called “bear-dogs” (Amphicyonidae) and “dog-bears” (Hemicyonidae), both of which were closely related to bears.

Skeleton image: Clemens v. Vogelsang from Liechtenstein / CC BY 2.0

Life reconstruction image: roman uchytel / Public domain

Other dog-like mammals include the “marsupial dogs” of the Borhyaenidae, a South American group of marsupial cousins, some of which had dog-like bodies and even habits. More recently, there were the extremely dog-like thylacines, also known as Tasmanian wolves, which lived in Australia until being driven to extinction by humans in the early 1900s.

Baker; E.J. Keller. / Public domain

Fritz Geller-Grimm / CC BY-SA 2.5

“Man’s Best Friend”

Finally and famously, the last several thousand years saw the rise of domesticated dogs, though exactly when, where, and how it happened are unclear. Research suggests the earliest domestication of dogs was probably a single event that could have occurred anywhere from 15,000 to 40,000 years ago, and probably in Europe or Asia. Whenever it happened, dogs are the earliest animals to be domesticated by humans.

Like cats, it’s thought that dog domestication may have started with certain wild wolves approaching human settlements for food, leading to selective pressure toward “friendliness” that might allow the wolves and humans to tolerate each other. Eventually, our two species grew closer until humans had dogs living alongside them and began controlling their breeding.

Domestication has a number of strange side effects on dogs. Read about it here:

Why Wolves Work Together While Wild Dogs Do Not

Dog Gazes Hijack the Brain’s Maternal Bonding System

Dogs ignore bad advice that humans follow

What makes dogs so friendly?

Wolves aren’t the only canid species to be domesticated! See also the famous long-running experiment to domesticate foxes in Russia.

Image: Popular Graphic Arts / Public domain

For more info check out the links below:

40 Million Years of Dog Evolution

How Dogs Came to Run the World

Ascent of the Dog

Russian foxes bred for tameness may not be the domestication story we thought

—

If you enjoyed this topic and want more like it, check out these related episodes:

We also invite you to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram, buy merch at our Zazzle store, join our Discord server, or consider supporting us with a one-time PayPal donation or on Patreon to get bonus recordings and other goodies!

Please feel free to contact us with comments, questions, or topic suggestions, and to rate and review us on iTunes!