Listen to Episode 117 on PodBean, YouTube, Spotify, or wherever else you can find it!

Several thousand living species – and many more fossils – are called “crabs,” but they don’t all share an evolutionary history. The crab-like body plan is a repeated trend in crustacean evolution, and there are differing opinions on what exactly counts as a “crab” and why natural selection keeps making them. This episode, we talk Crabs and Carcinization.

In the news

New species of beetle well preserved in Triassic poop

Tiny fossils hint that baby dinosaurs were growing up in the Arctic

“Dragon Man” might be a previously unknown lineage of ancient human

3,000-year-old man was attacked – and perhaps killed – by a shark

“True Crabs”

Many animals in many different arthropod families are called “crabs,” but only one group – crustaceans of the infra-order Brachyura – are officially the “true crabs.” These are close cousins of lobsters, but unlike their long-bodied lobster relatives, true crabs have compact, flattened bodies, with their pleon (their “tail” in a sense) folded under the body.

These are successful crustaceans, with around 7,000 known species alive today. Though most of them are marine, there are over 1,000 freshwater species, as well as several terrestrial lineages that spend all or most of their lives out of the water. Though crabs are famous for crawling on their numerous legs, many species are capable swimmers, with at least one pair of legs flattened into paddles.

Top right: Christmas island red crab (Gecarcoidea natalis), a species of land crab endemic to islands in the Indian Ocean. Image: John Tann, CC BY 2.0

Bottom left: Japanese spider crab (Macrocheira kaempferi), among the largest arthropods, reaching over 3m in leg span. Image: Charles Laigo, CC BY-SA 3.0

Bottom right: Yellowline arrow crab (Stenorhynchus seticornis), proof that crabs come in many shapes and sizes. Image: Nick Hobgood, CC BY-SA 3.0

True crabs seem to have gotten their start in the Jurassic Period, at a time where reefs were expanding and many marine animals were diversifying (including other crustaceans like lobsters). But crabs as we know them really get going in the Cretaceous, when nearly 80% of modern groups of Brachyura (“true crabs”) originated in a major diversification event, the so-called Cretaceous Crab Revolution. From then on, crabs have been a majorly diverse and widespread group of crustaceans, as they continue to be today.

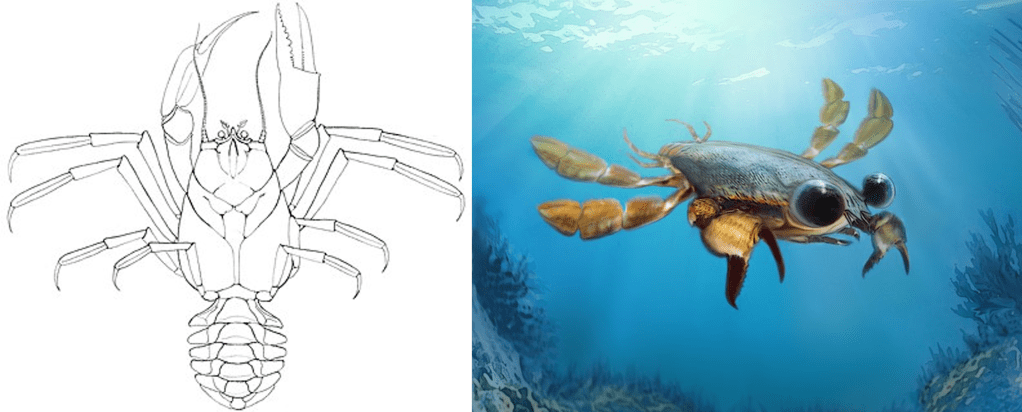

Right: Callichimaera, from the Cretaceous of the Americas, is unlike modern crabs, with its combination of large eyes, large claws, and a body built for swimming. It is evidence that crabs were already diverse in the Cretaceous. Art by Oksana Vernygora, CC BY 4.0

Crab-ification

Carcinization is a term first coined in 1916 to describe the evolution of a crab-like body plan, an evolutionary trajectory seen in far more animals than just the “true crabs.” King crabs, porcelain crabs, hermit crabs, squat lobsters, hairy stone crabs … these are all crustaceans that have independently evolved a crab-like body, despite not being “true crabs.” Like true crabs, these all seem to have evolved from lobster-like or shrimp-like ancestors. This trend even extends to fossils: Cyclida are an ancient group of strikingly crab-like crustaceans, but not true crabs either!

Top left: Red king crab (Paralithodes camtschaticus), a classic example of carcinization and an important food source. Image: Sasha Isachenko, CC BY-SA 3.0

Top right: Porcelain crab (Neopetrolisthes maculatus), lovely “crabs” with a habit of losing their limbs to escape predators. Image: Nick Hobgood, CC BY-SA 3.0

Bottom left: Squat lobster (Munidopsis tridentata), not a crab, and not a lobster.

Image: S. Bernhardt, Public Domain

Bottom right: Coconut crab (Birgus latro), land-dwelling hermit crabs and the largest terrestrial arthropods in the world. Image: Drew Avery, CC BY 2.0

Clearly, a crab-like body is advantageous – perhaps that compact body shape is good for avoiding predators by curling up the “tail” or by allowing the crab to hide in small spaces, or maybe it’s better for crawling around – but there’s a lot of discussion to be had about what counts as “crab” or “crab-like.” Not all scientists agree on which “crabs” are true examples of carcinization. And this is confounded even more by the fact that not all “true crabs” are truly “crab-like” – some are “decarcinized” like the long-bodied frog crabs, or the ancient Callichimaera (pictured above).

Learn more

How did crabs evolve ‘crabbiness’? It’s complicated

Videos about crab evolution from our friends at Eons and SciShow:

Why Do Things Keep Evolving Into Crabs? Eons

This Is What Peak Crustacean Looks Like SciShow

Crabs Keep Turning Into Land Animals! SciShow

Tsang et al, 2014. Evolutionary History of True Crabs (technical)

Scholtz 2014. Evolution of crabs – history and deconstruction of a prime example of convergence (technical)

Keiler et al, 2017. One hundred years of carcinization – the evolution of the crab-like habitus in Anomura (technical)

—

If you enjoyed this topic and want more like it, check out these related episodes:

- Episode 128 – the Deep Sea

- Episode 36 – Reefs

- Episode 70 – Convergent Evolution

- Episode 99 – Evolution of Insects

We also invite you to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram, buy merch at our Zazzle store, join our Discord server, or consider supporting us with a one-time PayPal donation or on Patreon to get bonus recordings and other goodies!

Please feel free to contact us with comments, questions, or topic suggestions, and to rate and review us on iTunes!