Listen to Episode 130 on PodBean, YouTube, Spotify, or wherever you can sniff it out!

With every breath you take, you collect information about your surroundings. This amazing ability is shared across the animal kingdom (and beyond). In this episode, we discuss the diversity and evolutionary history of our Sense of Smell.

In the news

Ichthyosaurs reached giant sizes surprisingly early in their evolution

The largest known millipede-cousin lived earlier than we thought

This Cretaceous bird had an unusually powerful tongue

Oviraptorid dinosaur embryos curled up like birds inside their eggs

Making Sense of Smell

All of our senses allow us to pick up information from our surroundings. In the case of smell (olfaction), what we’re detecting are chemical signals. The interior surfaces of our noses are home to special nerve cells that receive various kinds of airborne chemicals, from sources as variable as freshly cut grass, leaking gas, or morning breakfast. Once a scent has been detected, these nerve cells send a signal to the olfactory bulb, the portion of our brain that interprets smells.

Image by Patrick J. Lynch, CC BY 2.5

The main olfactory system is dedicated to detecting volatile chemicals – the ones that evaporate into the air. But there’s more: the accessory olfactory system is great at picking up non-volatile chemicals, including pheromones and other scents produced by animals. This system relies on the vomeronasal organ (also called the Jacobson’s organ), usually located just above the roof of the mouth. In humans, this organ is very small, sometimes non-existent, but for many animals, the vomeronasal organ is a major component of their smelling system, integral in a lot of animal-to-animal communication.

Left: Snakes’ tongues scoop chemicals out of the air and deliver them to the vomeronasal organ. Image from Distal Hill Gardens, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Right: Many mammals exhibit “Flehmen behavior,” raising their upper lip to draw scents toward their vomeronasal organ. Image by Yathin S Krishnappa, CC BY-SA 3.0

Most animals have the ability to smell, one way or another. Fish have nostrils, though they also have chemoreceptors across other parts of their bodies as well. Insects commonly use their antennae to pick up scents in their environment, and they can often also “smell” through their feet and other body parts. Birds are commonly thought to have poor sense of smell, but there are exceptions like New World vultures and New Zealand’s kiwis. Mammals are champion smellers, with extremely sensitive noses full of a diverse array of chemical receptors; mammals include some of the best sniffers in the world, such as bears and dogs. Even plants have the ability to pick up chemical signals from their environment, including communicative signals from other plants, although this isn’t quite “smell” as we experience it.

Smell Evolution

The ability to detect and interpret chemical signals from the environment is probably as old as life itself, so in that sense, life has always been able to “smell.” Olfactory systems like we see in animals today most likely evolved very early in animal evolution, as they’re present in just about every living branch of the animal family tree. A lot of research into the evolution of smell investigates the genes that code for scent-receptors, allowing scientists to explore periods of great expansions of smell genes (such as in the early history of mammals) as well as cases where the genetic repertoire of smell has been reduced (such as in modern humans, whales, and chickens).

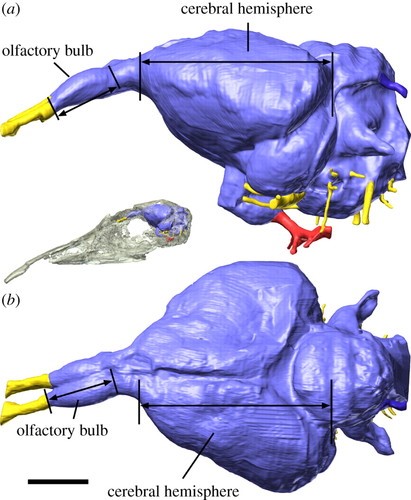

It can be difficult to determine the smelling capabilities of a fossil animal, since most of the smelling apparatus does not fossilize well, but some clues do exist. Paleontologists can measure the size and dimensions of a fossil animal’s nasal cavity – the larger the space, the more room for diverse scent receptors, the more likely a powerful sense of smell. Similarly, given a fossil skull with a well-preserved braincase, paleontologists can measure the size of the olfactory bulb of the brain, which is also generally larger in more skilled smellers. Such fossil evidence has been used to interpret smelling ability in early mammals, ancient birds, and a variety of other dinosaurs. Some fossil animals, like tyrannosaurs, are thought to have had excellent senses of smell.

Learn more

The Smell of Evolution, by Carl Zimmer

Padodara 2014. Olfactory Sense in Different Animals (technical)

Hoover, 2010. Smell with inspiration: the evolutionary significance of olfaction (technical, paywall)

—

If you enjoyed this topic and want more like it, check out these related episodes:

- Episode 68 – Evolution of Eyes

- Episode 52 – Sounds of the Past (Fossil Bioacoustics)

- Episode 121 – Brains

- Episode 88 – Evolution of Teeth

We also invite you to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram, buy merch at our Zazzle store, join our Discord server, or consider supporting us with a one-time PayPal donation or on Patreon to get bonus recordings and other goodies!

Please feel free to contact us with comments, questions, or topic suggestions, and to rate and review us on iTunes

So you could say that some animals do smell fear. Too bad we’ll probably never see that properly represented over cartoon animals or werewolves in film and TV.

Also, gastropods

LikeLike