Listen to Episode 214 on PodBean, YouTube, Spotify, or wherever you listen to your favorite podcasts!

Over and over again, evolution has provided animals with super-sized canines. This episode, we compare and contrast the various versions of Saber Teeth.

In the news

The Fossil Keeper’s Treasure, a children’s book by our friend Amy Atwater

Megalodon might have been even bigger – well, longer – than we thought

Vulture feathers mineralized within an ash deposit

What Big Teeth You Have

When we say “saber teeth,” we’re usually talking about the extra-large upper canines of certain predatory mammals. The most famous are the saber-toothed cats, but saber-toothedness has evolved many times in different lineages. In fact, saber-toothed predators tend to evolve a collection of similar features, altogether called the “saber-tooth suite,” including large, blade-like upper canines; enlarged incisors; muscular necks; bulky forelimbs; and more.

Top left: Skull of Homotherium. Image by Ghedoghedo, CC BY-SA 4.0

Bottom left: Skull of Machairodus. Image by Ghedoghedo, CC BY-SA 3.0

Right: Skeleton of Smilodon. Image by JJonahJackalope, CC BY-SA 4.0

Saber-toothed cats are felids (true cats) within the subfamily Machairodontinae. From 20 million years ago until around 10,000 years ago, saber-toothed cats were major predators on most continents, coming in a variety of sizes and living in a variety of habitats. They sported a spectrum of saber shapes. Some had short, round canines similar to modern big cats, while others – such as the famous Smilodon – had foot-long, blade-like canines, and other species occupied every point in between.

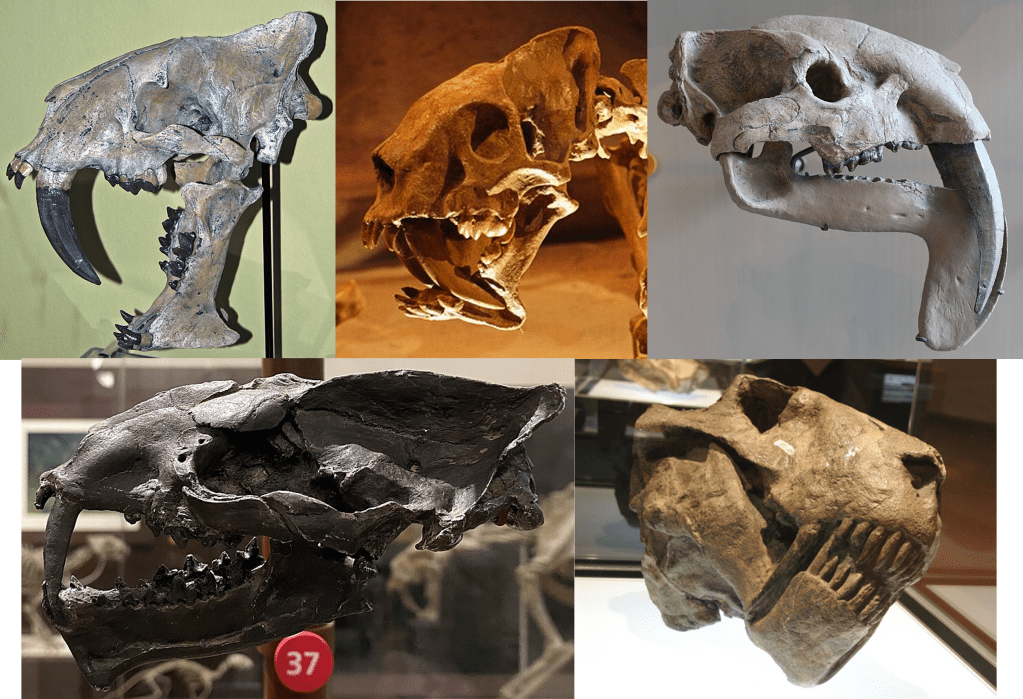

Top left: Skull of the nimravid Hoplophoneus. Image by James St. John, CC BY 2.0

Top middle: Skull of the barbourofelid Barbourofelis. Image by Dallas Krentzel, CC BY 2.0

Top right: Skull of the near-marsupial Thylacosmilus. Image by Jonathan Chen, CC BY-SA 4.0

Bottom left: Skull of the “creodont” Machaeroides. Image by Ryan Schwark, CC0

Bottom right: Skull of the non-mammal gorgonpsian Smilesaurus. Image by MaropengSA, CC BY 2.0

The question of how these predators wielded their canines has been the subject of much debate and research. Cats with shorter canines likely hunted similarly to modern big cats, clamping down and holding onto prey with a killing bite. Longer-sabered species are thought to have used a slightly different technique, holding prey still with their powerful arms and using extensive neck muscles to drive their canines into vulnerable soft spots, dealing fatal wounds. Similar strategies might have been used by nimravids and barbourofelids, saber-toothed cousins of cats sometimes called “false saber-toothed cats.”

On the other hand, the “marsupial sabertooth” Thylacosmilus (technically a close cousin of true marsupials) had a very different dentition that might have been less useful for a killing blow and better-suited to prying open carcasses. And the not-quite-mammalian gorgonopsians, despite their large upper canine-like teeth, had skulls and jaws more similar to crocodiles and carnivorous dinosaurs, and so they may have hunted quite differently from their distant cat relatives.

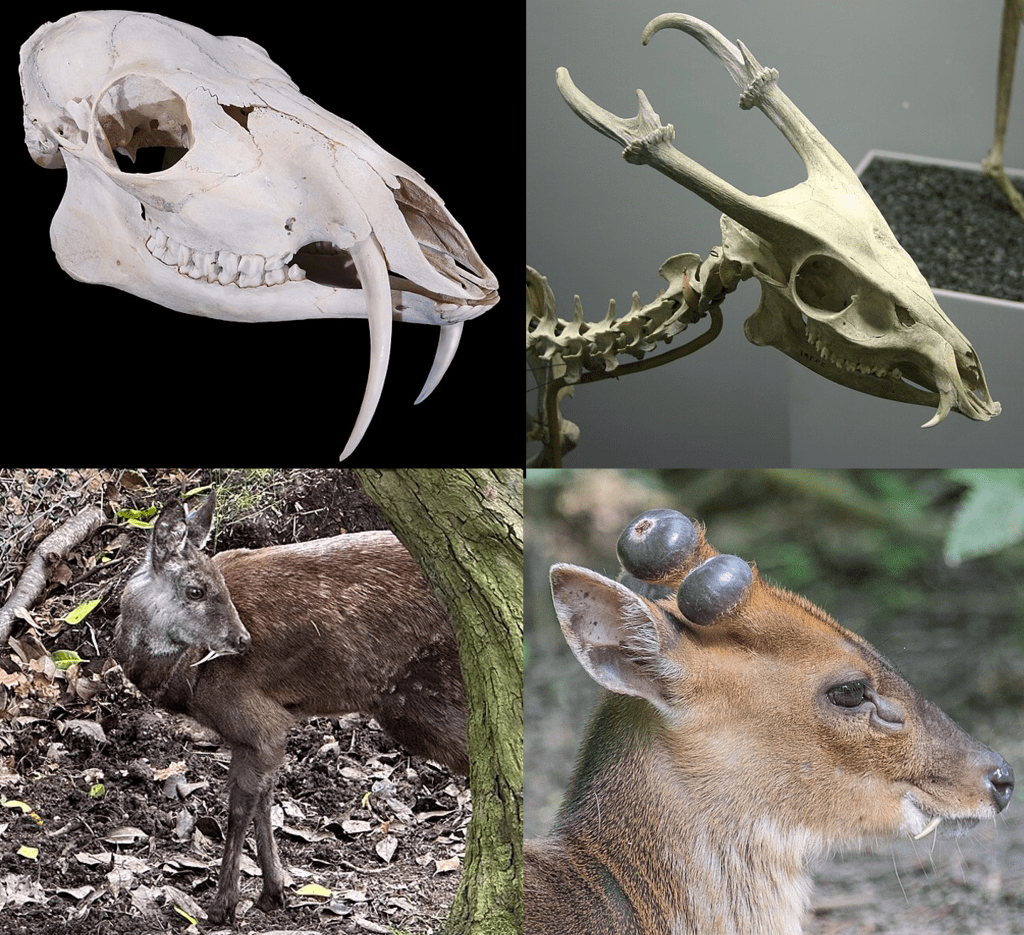

Left: The Triassic near-mammal dicynodont Diictodon. Image by Nkansahrexford, CC BY 3.0

Right: The Eocene herbivorous mammal Uintatherium. Image by Shadowgate, CC BY 2.0

Saber teeth aren’t just for predators. The near-mammal dicynodonts and the rhino-like uintatheres, both ancient herbivores, had enlarged upper canines that were most likely used for display and combat among their own species, similar to the way modern pigs and hippos use their enlarged canines, which we typically call “tusks.” Enlarged upper canines have also evolved several times among deer and their relatives, and in some species the canines can even swivel out of the way when it’s time to eat.

Bottom left: Live musk deer. Image by EspenÅberg, CC BY-SA 4.0

Top right: Skull of barking deer (muntjac). Image by Ryan Somma, CC BY-SA 2.0

Bottom right: Live barking deer. Image by Johannes Maximilian, CC-BY-NC-ND

Another common question is whether ancient animals’ saber teeth were covered or exposed when their mouths were closed. Through detailed study of fossil and modern animal anatomy, recent research has concluded that species with particularly long teeth, such as Smilodon, might have had perpetually-exposed canines like musk deer, but that many other saber-toothed animals’ canines would have been hidden under their lips, similar to modern big cats and hippos.

Left: Skull and life appearance of Homotherium.

Right: Skull and life appearance of Megantereon.

Images from Antón et al 2022 and 2024.

Learn More

Functional performance of saber teeth and the open access paper

The double-fanged adolescence of saber-toothed cats and the open access paper

Thylacosmilus interpreted as not a saber-toothed predator and the open-access paper

Concealed weapons: the life appearance of the saber-toothed cat Homotherium (technical, open access)

Exposed weapons: the life appearance of the saber-toothed cat Megantereon (technical, open access)

Hypercanines: Not just for sabertooths (technical, open access)

Convergence obscures functional diversity in sabre-toothed carnivores (technical, open access)

Changing ideas about the evolution and function of saber-toothed cats (technical, open access)

__

If you enjoyed this topic and want more like it, check out these related episodes:

We also invite you to follow us on Facebook or Instagram, buy merch at our Zazzle store, join our Discord server, or consider supporting us with a one-time PayPal donation or on Patreon to get bonus recordings and other goodies!

Please feel free to contact us with comments, questions, or topic suggestions, and to rate and review us on Spotify or Apple Podcasts!

Leave a comment