Listen to Episode 60 on PodBean, Spotify, YouTube, or that other podcast player you like!

Turtles are so weird and wonderful. They’ve been around since the Triassic Period, but right from the start, they went down an anatomical pathway that has made them unlike any other animal. They took their strange body shape and diversified into an incredible array of shapes and lifestyles. And despite a fairly good fossil record and plenty of genetic data, their evolutionary relationships remain mysterious. This episode, it’s all about Turtles.

In the news

The famous crocodilian “death roll” is apparently a very ancient behavior.

A new species of Miocene mammalian apex predator was the size of a rhino.

A strange Cretaceous crab-cousin reveals surprising ancient diversity in crabs.

The Gray Fossil Site rhino is officially a new species!

BONUS: This 1500-year-old human poop has way more snake in it than expected.

Turtles

There are around 350 recognized living species of turtles, and they live all over the world, in land and sea, jungles and deserts. All turtles share several unusual characteristics: they have toothless jaws with a horny beak; they’re all egg-layers; and they’ve completely restructured their torsos to form the iconic turtle shell.

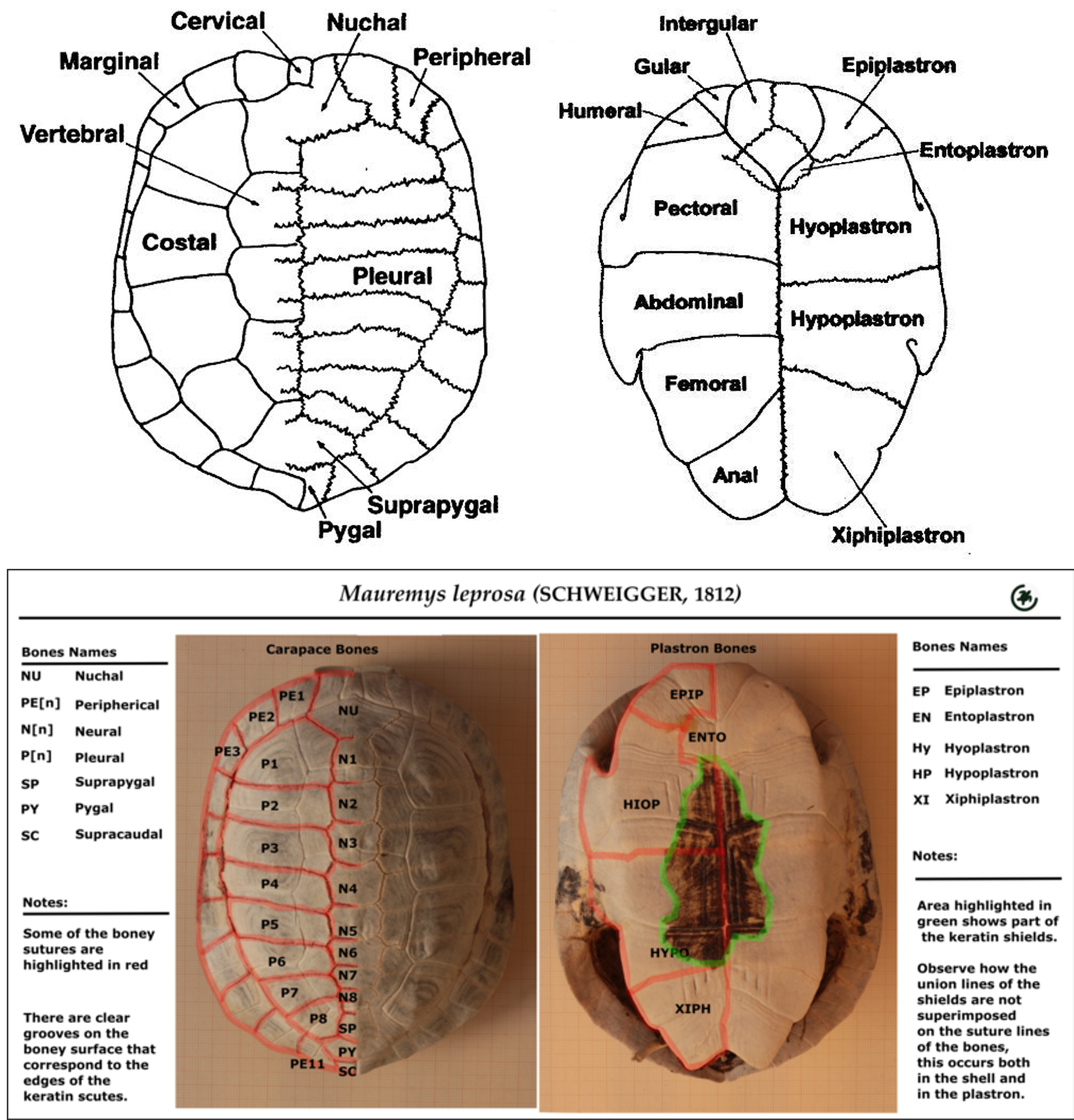

The turtle shell is a remarkable evolutionary innovation. It comes in two parts – carapace on top and plastron on bottom – each made of a puzzle of fused bones. The bulk of the carapace is made of the turtle’s rib cage, each rib lengthened and expanded to form a solid wall, while the corresponding vertebrae are fused into the central bones of the shell. The carapace is similarly derived in part from gastralia (belly ribs). This means that a turtle that can retract inside its shell is pulling nearly its entire body inside its own rib cage.

Weird.

Turtle Family Ties

There are more than a dozen living families of turtles and plenty of extinct ones. They are split into two varieties: pleurodires and cryptodires. Both can often pull their heads back into their shells, but pleurodires have necks that bend sideways and fold alongside the body inside the shell, while cryptodire necks fold up and down as they pull their heads straight back into their shell. You can see a visual of this on page 3 of this document.

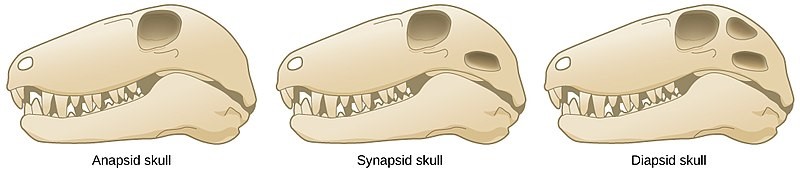

Maybe the most contentious thing about turtles is where they fit in the reptile family tree. Classically, they were grouped with other anapsids (see the image below) at the very base of the reptile lineage. But more recent genetic and fossil finds suggest they belong with diapsids, though exactly which ones is unknown. Recently, many analyses have indicated turtles are close relatives of archosaurs (crocs and dinos), but there still isn’t a true consensus.

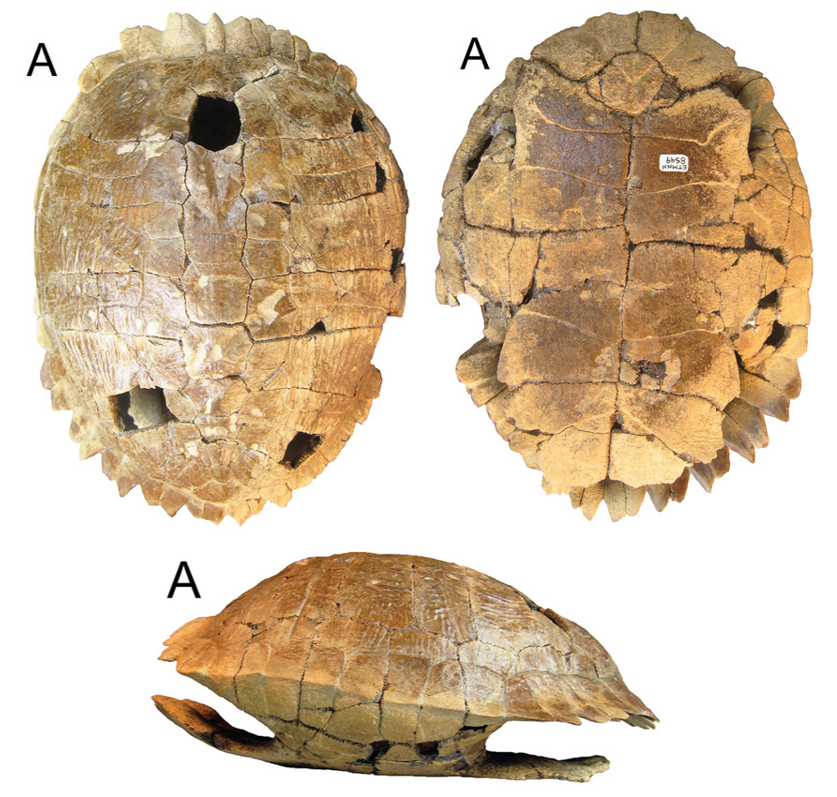

Fossil Turtles

At the very base of the turtle fossil record are a handful of specimens that hint at their early evolution. Eunotosaurus, Odontochelys, Proganochelys, and others suggest the gradual development of the shell from expanded ribs and gastralia, the gradual loss of those temporal fenestrae in the skull, the loss of teeth and development of the beak, and even the shift to a more turtle-like breathing system. They don’t quite answer all the questions about why the shell evolved, what the earliest turtles were doing ecologically, or where on the tree of life turtles belong, but it’s a start.

From the Jurassic onwards, turtles are found all over the world. The fossil record is littered with bits of turtle shell, including at our favorite fossil locality: the Gray Fossil Site! Our buddy Dr. Steve Jasinski published on a new species in 2018, Trachemys haugrudi, named after our friend Shawn (you can hear him in Episode 13). And our old professor, Dr. Blaine Schubert, helped name another new species: Sternotherus palaeodorus.

More Turtles

Various news reports on some famous fossil turtles:

Eunotosaurus

Odontochelys

Trachemys haugrudi from the Gray Site

Sternotherus palaeodorus from the Gray Site

A couple of technical papers:

Joyce 2015. The origin of turtles: a paleontological perspective.

Lyson et al 2016. The origin of the turtle breathing system.

Jasinski 2018. The Gray Fossil Site slider turtle.

—

If you enjoyed this topic and want more like it, check out these related episodes:

We also invite you to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram, buy merch at our Zazzle store, join our Discord server, or consider supporting us with a one-time PayPal donation or on Patreon to get bonus recordings and other goodies!

Please feel free to contact us with comments, questions, or topic suggestions, and to rate and review us on iTunes!

This is only the third episode I’ve listened to since discovering you (I think via Tet Zoo) and I say bravo! Turtles are, of course, the greatest animals that have ever existed but they do not garner the attention they deserve. Now if only you could do 350-odd episodes covering, in depth, each extant species and subspecies, then tackle the extinct ones… well, even if you don’t, I still love the podcast.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, I forgot one thing…shame on you for releasing this episode on May 4th, talking about the Leatherback’s throat, but failing to make the comparison to the Sarlacc, the Great Pit of Carkoon, from Return of the Jedi (original release, not that damned special edition). What kind of nerds are you, anyway?!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for listening! Turtles certainly are underappreciated wonderful weirdos. And alas, we did overlook an opportunity to make a Sarlacc reference. This is why we keep our audience full of helpful nerds.

LikeLike

Dang! Those hyaenodont teeth give a whole new meaning to “nom nom nom.”

LikeLiked by 1 person