Listen to Episode 61 on PodBean, Spotify, YouTube, or that other podcast player you like!

Ancient animals didn’t just stand around. They moved, interacted, hunted, reproduced, and did all the things animals do. It’s easy to image all of that information is lost to time, but there are all sorts of ways paleontologists can find those clues. In this episode, we’re exploring the tools, techniques, and amazing fossil finds that help us understand Behavior in the Fossil Record.

In the news

The first known Denisovan jaw!

Ambopteryx longibrachium, a new “bat-winged” dinosaur from China.

Ice Age animals from the bottom of a flooded cave in Mexico.

Computer models, a baby ostrich, and a robot dinosaur reveal a potential origin to flapping in winged dinosaurs.

Studying Behavior

The study of behavior is known as ethology, and it’s just as important in understanding the lives of animals as they study of their bones and bodies. Georges Cuvier was one of the first to suggest that we could study behavior in the fossil record.

He suggested that we could use animals’ morphology to understand their behavior, since “form follows function.” He’s not wrong, but it’s also not that simple. Animal behaviors can be as varied as the diets of brown bears or as unexpected as the habits of fruit-eating crocodilians. So getting behavioral information out of fossils is tricky … but not impossible.

Here are a few of the main categories of evidence we use to interpret fossil behavior.

The skeleton

There are some physical features that act as pretty reliable indicators of behavior. Limb proportions and dental features can give hints about how an animal moved and what it ate, while stress fractures and muscle scarring on bones can tell you how an animal was using its body and what pressures it encountered.

But you have to be careful. New adaptations don’t often arise until after a behavior has started. Evidence has shown, for example, that ancient elephants began eating grass millions of years before they finally evolved the dental features for their new diet.

Modern Analogues

Sometimes, the best way to understand the behavior of extinct species is to compare them to living species. An ancient animal with wings is probably behaving similarly to modern winged animals. Animals are also likely to share a lot with their living relatives, so ancient turtles were probably behaving like modern turtles.

But some ancient animals like dinosaurs aren’t very similar to living animals, so we have to try a few different approaches. If you’re trying to understand how a giant dinosaur moved, for example, you might compare it to modern large animals like elephants.

And when paleontologists want to interpret dinosaur behavior or physiology, they can use a technique called phylogenetic bracketing. This involves looking at their closest and next-closest relatives to find features they share. The logic here is that if birds (living dinosaurs) and crocodilians (dinosaurs’ closest living cousins) share a heritable feature (say, their respiratory system or their instinctual habits), it’s likely their last common ancestor had that feature, too. And that ancestor also gave rise to all other dinosaurs, so perhaps they inherited the same traits.

It’s not a perfect approach. Sometimes traits can be lost in certain parts of the family tree, and other times similar traits can appear multiple times through convergent evolution. But in concert with other approaches, phylogenetic bracketing can be very useful.

Computer Models

With information from fossil and modern animals, scientists can digitize the information to simulate the physical limitations of the fossil. In this way, they can analyze features like bite forces, walking posture and speed, and even physiology. We can even go the extra step and build robots to test their results!

Ichnofossils

Ichnofossils are traces left behind by animal behavior. These come in many forms, which can be classified using the Seilacherian System.

Probably the most famous ichnofossils are things like footprints and burrows left behind by animals moving through sediment. Some interesting examples include footprints from herds of sauropods, an ornithopod family, and some that showed how pterosaurs walked. There are even trackways that have been interpreted as evidence of display behavior.

Trackways not only tell us about where an animal walked, they can also be used to determine its speed and posture.

Other forms of ichnofossils include feeding traces, which can be evidence of attacks from predators, competition, and even cannabilism, and coprolites, which can tell us about diet and digestion.

Ethofossils

In extremely rare cases, we can find fossils of animals preserved in the middle of doing something, or shortly afterward. These are sometimes called ethofossils, fossilized behavior.

There are lots of great examples:

Feeding Behavior and Stomach Content

– Snake preserved while possibly hunting baby dinosaurs

– Large amphibian choking on a smaller member of its species

– Fish that swallowed a fish a bit too large for them to handle

– A shark that ate and amphibian that had eaten a fish

Social Behavior

– Social marsupial cousins

– A juvenile group of ornithomimid dinosaurs

– Potential pack hunting in Deinonychus, though this is disputed

Parental Care

– The caring Oviraptor guarding its eggs

– Maiasaura, the “good mother reptile”

– A traveling family of dinosaurs

– A dinosaur parent with young in a burrow

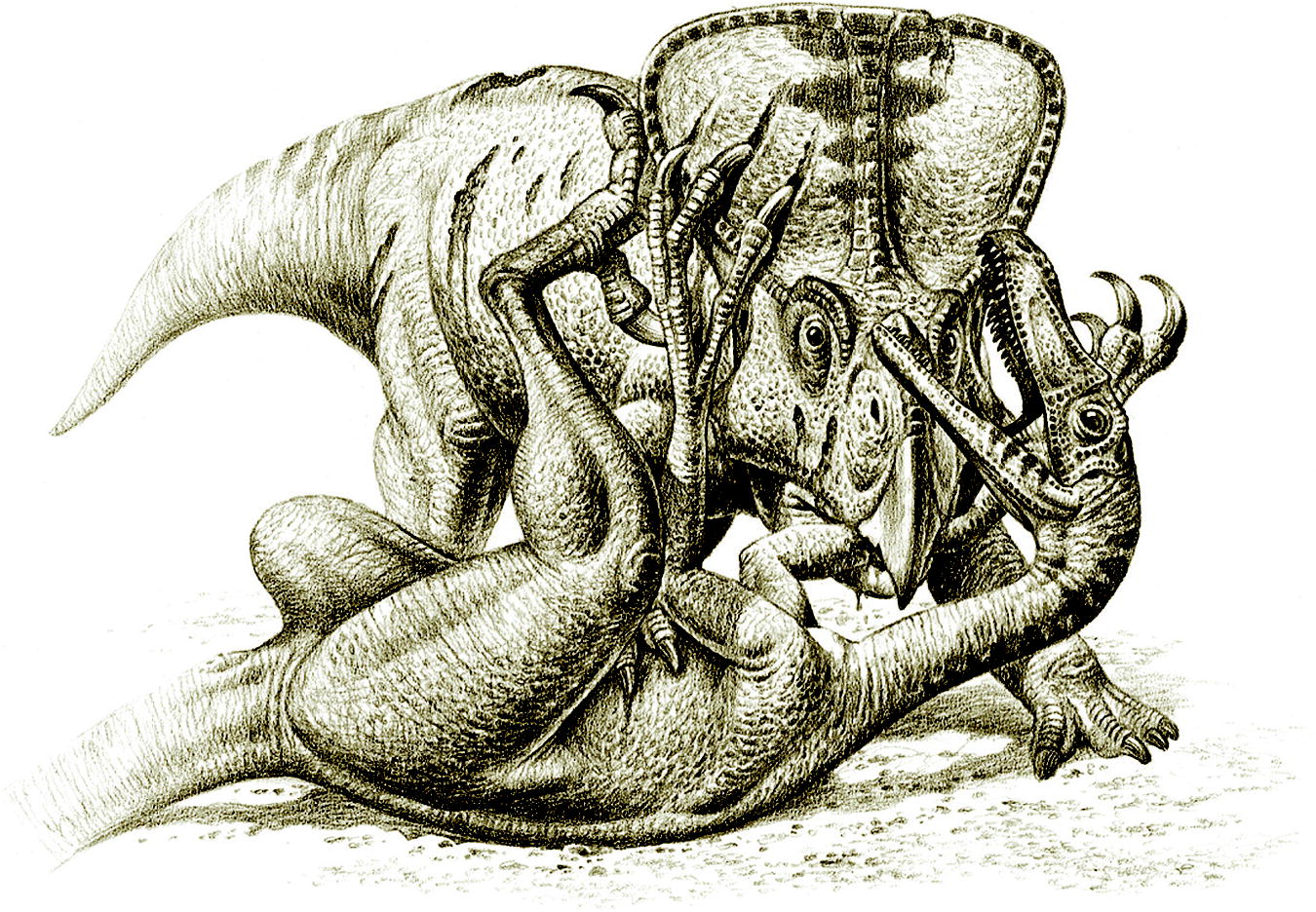

Probably the most famous behavior fossil is “The Fighting Dinosaurs” of Mongolia, which preserves the skeletons of Velociraptor mongoliensis and Protoceratops andrewsi apparently in the middle of a fight. The skeletons are intertwined with the Velociraptor grabbing the head and kicking at the neck of the Protoceratops, while the Protoceratops bites the Velociraptor‘s right arm. Only one other fossil has ever come close to preserving such a dynamic moment in fossil history, the “Dueling Dinosaurs” of the Hell Creek Formation, but unfortunately this specimen remains in private storage so has yet to be analysed.

And more!

If you’d like to look into more sources about fossil behavior take a look at these:

Bird behaviour, the ‘deep time’ perspective

How do we know what we know about dinosaur behaviour?

Fossil dinosaur slept like a bird

Embryos of an Early Jurassic Prosauropod Dinosaur and Their Evolutionary Significance

Tyrannosaurus was not a fast runner

Actually, You Could Have Outrun a T. rex

Tyrannosaurus rex ate meat but also accidentally planted fruit

Social Behaviour in Dinosaurs – with David Hone:

—

If you enjoyed this topic and want more like it, check out these related episodes:

- Episode 52 – Sounds of the Past (Fossil Bioacoustics)

- Episode 63 – Sexual Selection

- Episode 126 – Mimicry

- Episode 133 – Symbiosis

We also invite you to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram, buy merch at our Zazzle store, join our Discord server, or consider supporting us with a one-time PayPal donation or on Patreon to get bonus recordings and other goodies!

Please feel free to contact us with comments, questions, or topic suggestions, and to rate and review us on iTunes!

One of the behavior questions I tend to find annoying is whether T. rex was a scavenger or a carnivore, with the underlying assumption that this is an either-or question: either T. rex was a carnivore, attacking and killing live prey or a scavenger, feasting on other predators’ leavings but not something that did both.

While there are carnivores that don’t scavenge, which I understand is the case with frogs, snakes, and spiders, crocodilians, Komodo dragons, and goannas all scavenge. So do lions, raptors, and domestic cats.

LikeLike