Listen to Episode 210 on PodBean, YouTube, Spotify, or wherever you listen to your favorite podcasts!

The evolution of mineral tissues is not only responsible for the incredible diversity and success of vertebrate animals, but also for their extraordinarily informative fossil record. This episode, we explore some of paleontology’s favorite body parts: Bones.

In the news

A pterosaur bone with a croc bite mark

Isotopes show Australopithecus ate mostly plants

Mammal outer ears are built with fish gill genes

New techniques characterize reptile diets

Bones!

Bones are a foundational (literally!) feature of vertebrate animals. They provide structural support to the body, sturdy anchors for musculature, defensive walls around internal organs, and a reservoir of minerals and other resources. They are also the primary reason that paleontologists have so much information about vertebrate evolution.

Bone is a type of connective tissue, composed of organic material mixed with calcium phosphate minerals. Alongside dentine and enamel (in our teeth), bones are the primary “hard tissues” of vertebrates. But bone isn’t just solid material, it’s a complex and active tissue with blood vessels, nerves, and a specialized series of bone cells that develop new bone tissue and break down and recycle old bone. All of this activity forms an intricate and ever-changing pattern of tissue within bone.

The evolution of bone was not a simple, single step from no-bone to bone. During the Early Paleozoic Era, early vertebrate animals developed a wide variety of mineralized tissues, including rigid supports for fins and gills, bony plates covering the head or body, and tooth-like structures in the mouth. These tissues commonly incorporated minerals similar to bone, dentine, enamel, and hard cartilage. Over time, these hard tissues gave rise to true bones and teeth as we know them, and bony fish gradually developed full internal skeletons that would give rise to the bony insides of all land vertebrates.

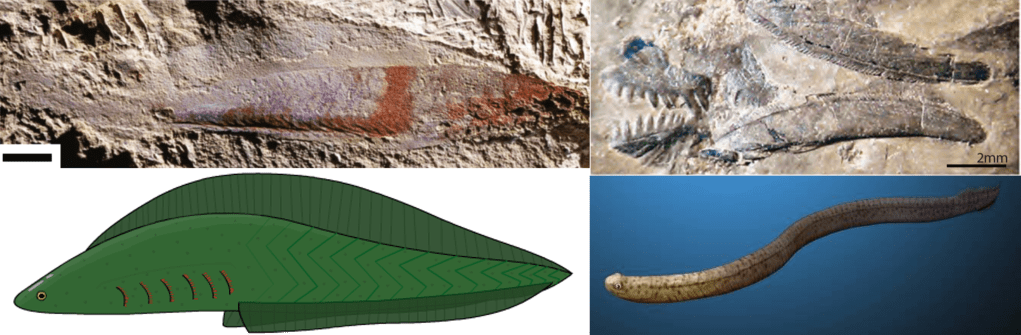

including rigid gill supports in myllokunmingiids and tooth-like structures in conodonts.

Top left: Fossil of Myllokunmingia. Image from Saleh et al 2022

Bottom left: Art of Myllokunmingia by Giant Blue Anteater

Top right: Fossil conodont with teeth. Image from Briggs et al 2018

Bottom right: Art of a conodont by Nobu Tamura, CC BY-SA 4.0

Image from Donoghue and Keating 2014.

Hard tissues are very common in the fossil record. Because of their rigid structure and stable composition, bones and other mineralized tissues often resist decay and scavenging long enough to become buried within sediment, and they are better able to survive the process of burial as well.

Because bones are so essential to the lives of vertebrate animals, paleontologists can gather an incredible amount of information from them. Unique features on bones can help identify a species; the shape of joints and muscle attachment sites can inform how ancient animals moved; the anatomy of limb bones, jaw bones, and more can reveal adaptations to specific lifestyles; bones can retain evidence of injury or disease or changes throughout the life of an animal; cavities within bone can show the shape of internal organs such as brains or inner ears; the chemical structure of bone can be used to infer ancient animal diets, physiology, migration paths, and more.

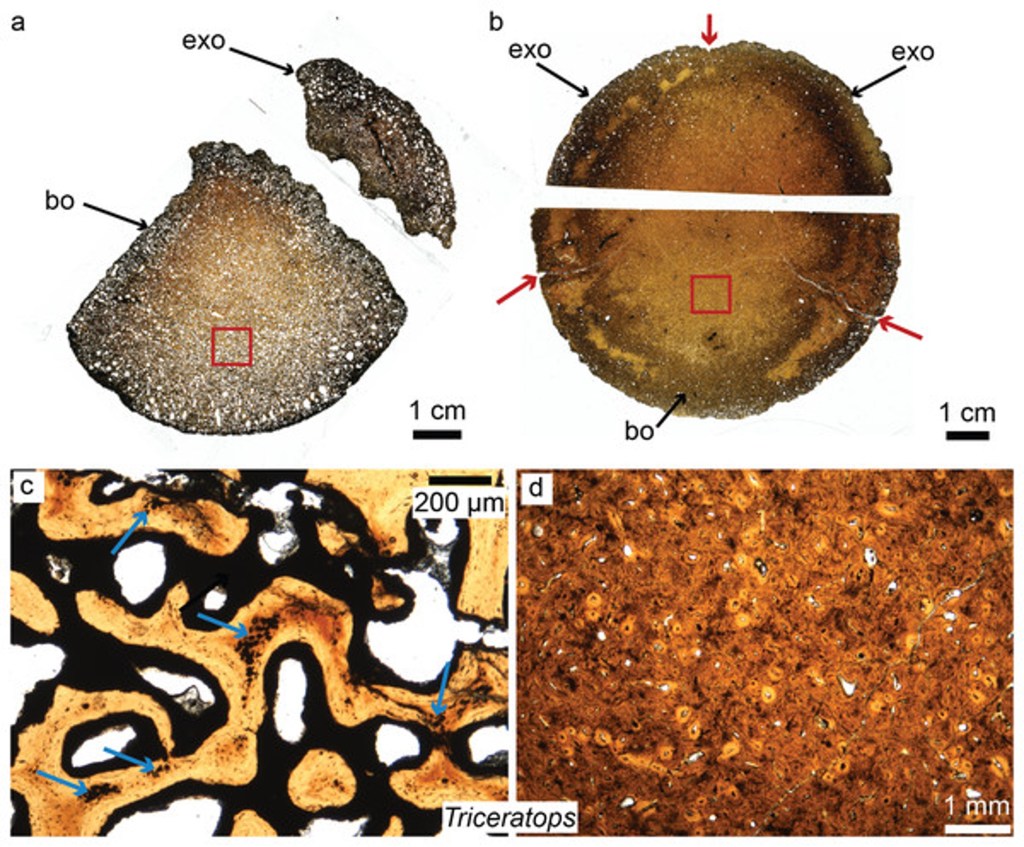

Fossilization can also preserve the microscopic structure of bone, including the distribution of tissues and the arrangement of cells and blood vessels. The study of microscopic features of fossil tissues is paleohistology, normally performed with thin slices of bone or internal scanning technology. These studies can be used to interpret ancient animal growth patterns, reproductive habits, physiology, structural adaptations, and lots more.

Scale bar = 100um. Image from Haridy et al 2021.

Image from Bailleul et al 2019.

Learn more

Structure of Bone

Anatomy: Cartilage

Where did bone come from? (technical, open access)

The ‘biomineralization toolkit’ and the origin of animal skeletons (technical, open access)

Dinosaur paleohistology: review, trends and new avenues of investigation (technical, open access)

Vertebrate Skeletal Histology and Paleohistology (Book)

Bone Apatite Nanocrystal: Crystalline Structure, Chemical Composition, and Architecture (technical, open access)

__

If you enjoyed this topic and want more like it, check out these related episodes:

We also invite you to follow us on Facebook or Instagram, buy merch at our Zazzle store, join our Discord server, or consider supporting us with a one-time PayPal donation or on Patreon to get bonus recordings and other goodies!

Please feel free to contact us with comments, questions, or topic suggestions, and to rate and review us on Spotify or Apple Podcasts!

Leave a comment