Listen to Episode 179 on PodBean, YouTube, Spotify, or wherever you listen to your favorite podcasts!

In order for living cells and tissues to operate properly, they require certain temperatures, so organisms spend lots of time and energy balancing heat and cold. In this episode, we discuss diversity, adaptations, and ancient history regarding the important process of Thermoregulation.

In the news

Soft robots help interpret early echinoderm locomotion

Footprints are the oldest known bird fossils in Australia

Shark genes and the evolution of taste receptors

New early dinosaurs shed light on egg evolution

Temperature Control

The cells, organs, and tissues of living things rely on a variety of physical and chemical processes, and if it gets too hot or too cold, things stop functioning properly. So, organisms spend a lot of time and energy making sure their body temperature is just right.

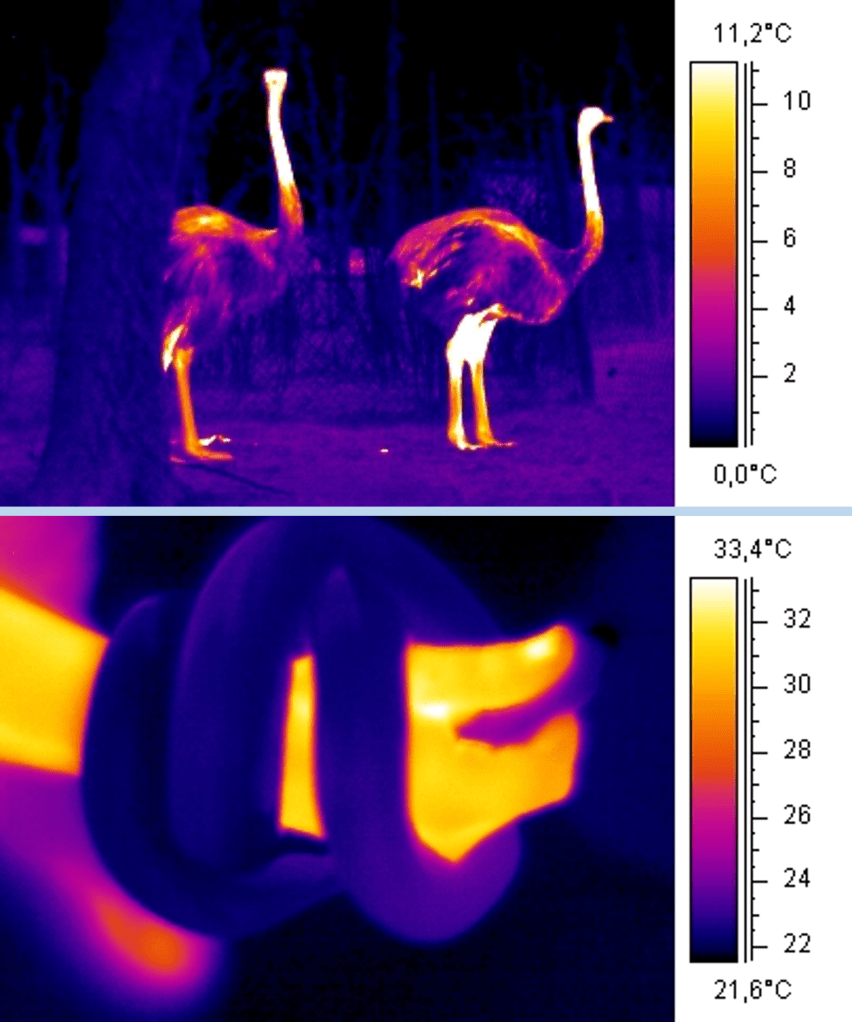

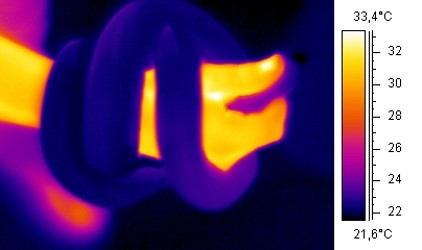

Bottom: Thermal image of a human arm holding a snake. Notice that the human’s body temperature is much higher than the snake’s. Image by Arno / Coen, CC BY-SA 3.0

Animals are commonly referred to as either “warm-blooded” or “cold-blooded,” referring to a relatively high or low typical body temperature. Naturally, things are more complicated than this, and there are other terms to refer to more specific aspects of animal thermoregulation:

Endothermic animals get most of their body heat from internal processes, while ectothermic animals get most of their body heat from their surroundings.

Homeothermic animals typically maintain a stable body temperature, while poikilothermic animals have more variable temperatures.

Tachymetabolic animals have high rates of energy-consuming metabolic reactions, while bradymetabolic animals have lower metabolic rates.

“Warm-blooded” species (like mammals and birds) tend to be endothermic, homeothermic, and tachymetabolic, while “cold-blooded” species (like fish, amphibians, and reptiles) tend to be ecothermic, poikilothermic, and bradymetabolic. And of course, there are plenty of exceptions and in-betweens. For example, tuna are somewhat “warm-blooded” fish, while naked mole rats are “cold-blooded” mammals, and many species are heterothermic, switching between thermoregulatory modes from time to time.

Right: Many animals have specialized anatomy to help with thermoregulation. Elephants’ big ears can capture or radiate heat as needed. In this thermal image, notice how the ears are colder than the rest of the body. Image from Janel Lefebvre et al., 2023

A wide variety of adaptations help organisms to manage their body temperatures. Fur and blubber insulate the body to keep heat in; big ears or wings can catch or radiate heat as needed; sweating and panting expose moisture to the air, which removes heat as it evaporates; and many organisms actively seek out warm or cool surroundings to suit their needs.

Internal heat can also be generated in a variety of ways. Birds and mammals – the classic “warm-blooded” animals – get most of their heat from chemical reactions that occur in tissues all over the body. Many endothermic fish have specialized “heat organs,” usually in their heads, that perform similar heat-generating chemical reactions. Many vertebrates will shiver, activating their muscle tissues to produce energy that is released as heat. Some insects will flap or “shiver” their wing muscles to warm themselves up. There are even species of plants known to use internal reactions to produce heat.

Maintaining high body temperatures and a high metabolic rate means that “warm-blooded” animals can sustain high levels of activity, even when the surroundings are cold. The trade-off is that this lifestyle requires lots of fuel – that is, food – and the animal can run the risk of overheating. On the other hand, “cold-blooded” animals can’t be as consistently active, but they can survive on less frequent meals.

What About the Past?

To interpret the thermoregulatory strategies of ancient animals, paleontologists can look for features associated with “warm-blooded” or “cold-blooded” species today: the arrangement of bone tissues can reveal slow or fast growth rates; fossils sometimes preserve insulating structures like fur, feathers, or blubber; the anatomy of an ancient species can hint at a high- or low-activity lifestyle; and the chemical composition of bones and teeth can indicate the temperature at which those tissues formed; just to name a few.

One major focus of research is the transition from “cold-blooded” to “warm-blooded” strategies, something that has happened several times in the past. This research often focuses on a handful of particular groups of ancient life.

Top right: Early synapsids ultimately gave rise to mammals. At some point along the way, this lineage evolved endothermy and other mammalian features. Image by Nobu Tamura, CC BY-SA 3.0

Bottom left: Ichthyosaurs and other marine reptiles are thought to have likely been endothermic to some extent, given that they have bodies (and probably lifestyles) similar to many endothermic fish and aquatic mammals. Image by Dmitry Bogdanov, CC BY 3.0

Bottom right: Since birds are “warm-blooded,” it’s probable that their dinosaur relatives had similar thermoregulatory strategies. Image by Mette Aumala, CC BY-SA 4.0

For all of the above groups, there has been fossil evidence to suggest they maintained high body temperatures and high metabolic rates to some extent.

Learn more

Dinosaur Physiology, with discussion of thermoregulation strategies

The evolution of mechanisms involved in vertebrate endothermy, 2020 (technical)

The thermoregulation system and how it works, 2018 (technical)

Whole-body endothermy: ancient, homologous and widespread among the ancestors of mammals, birds and crocodylians, 2021 – this paper argues that endothermy was more widespread in ancient vertebrates than normally recognized (technical, open access)\

__

If you enjoyed this topic and want more like it, check out these related episodes:

- Episode 47 – Early Synapsids (“Proto-Mammals”)

- Episode 61 – Behavior in the Fossil Record

- Episode 113 – Paleoclimate

We also invite you to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram, buy merch at our Zazzle store, join our Discord server, or consider supporting us with a one-time PayPal donation or on Patreon to get bonus recordings and other goodies!

Please feel free to contact us with comments, questions, or topic suggestions, and to rate and review us on iTunes.

Leave a comment